Still Life

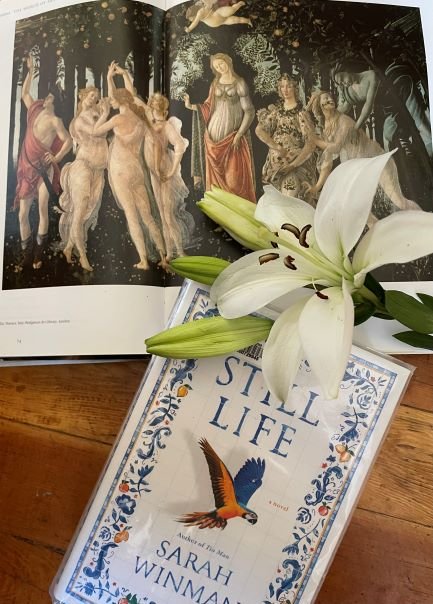

I recently picked up Sarah Winman’s recent historical fiction novel: Still Life (2021). In addition to its beautiful cover of flowers and parrot, the reference to the world of painting in its title immediately piqued my interest, as did its setting. As I read, it’s depth of characters and place transported me to mid-20th-century London and Florence, and I didn’t want to leave. I wanted to nestle in and live with protagonist, Ulysses, and the myriad friends and relations he gathers around him.

This novel begins in 1944 Italy as WWII comes to a close. Readers meet English art historian, Evelyn Skinner, who at nearly sixty-four years of age is holed up in a modest albergo in the Tuscan countryside awaiting Florence’s liberation from Nazi occupation. This opening scene leads Evelyn into the life of young British Private, Ulysses Temper, for an evening that promises to ripple through both their lives.

Art and creatives wander in and out of this novel as decades pass. Ulysses and Evelyn continue to ramble ever nearer to reconnecting. The trajectory of the novel promises that they will. Even the first epitaph Winman selects for her novel suggests as much: “Two people pulling each other into Salvation is the only theme I find worthwhile. – E. M. Forster, Commonplace Book.” But along the way to that reunion, the reader accompanies each character through life and witnesses the memories and relationships they cherish most.

From the beginning, Still Life interacts with the world of art. On the second page, for example, Evelyn mentions that the allies have located Botticelli’s Primavera. The importance of capturing the commonplace domestic alongside the grand, life-altering moments emerges as a theme. Through the Evelyn’s art historian voice, Winman investigates the impact of art, especially still life art, in reflecting the everyday life of women, the patrons of that domestic sphere.

If Still Life is a novel that investigates the domestic, it is unsurprising that it is also a novel about family. In Winman’s novel, Ulysses and Evelyn both collect a family of individuals whom they love, but with whom they do not share blood. Winman certainly celebrates the notion that we may choose our family. The cast of characters with whom Ulysses, in particular, connects deeply—beyond Evelyn—include his fiery lost-soul beloved (Peg), a rough-and-tumble pub owner (Col), amateur scientist (Cress), piano man (Pete), Florentine dandy (Massimo), the kid (Alys), and a Shakespeare-quoting blue-fronted Amazonian parrot (Claude). From this rowdy crew, Ulysses constructs a family and a beautiful life full of love.

Speaking of: Love in all its complex iterations is the primary theme in Still Life. Winman’s novel explores same-sex love, unrequited love, abandoned love, parental love, and the love of deep-rooted friendship. All the love in Still Life is life-affirming, beautiful, and presented as perfectly suited to the natural order. In fact, I found the normalization with which Winman crafts her various characters and their love interests distinctly notable and worthy of applause. While this novel certainly includes plenty of reference to the intimate lives of queer characters, it is not unilaterally LGBTQ+ fiction. Rather, in developing the many domestic loves of her characters, Winman reflects the truth that love is complex and wildly intimate. Characters, as real people, love who they love; sexual orientation does not limit identity of either the characters nor the novel itself. Still Life is a book about love and its incredible power to move us, unite us, connect us, and compel us “into Salvation,” as Forester describes it in Winman’s chosen epigraph.

The novel’s action centers first on Tuscany then gritty East London and back to Florence with momentary escapades to Bloomsbury London. Winman weaves in a hefty amount of reference to Forster’s A Room With A View; I may dive down the literary reference rabbit hole and reread it at some point this spring. By the novel’s close Forster has walked into Still Life as a side character himself. One of my favorite aspects of this novel is it’s sense of place which is nearly tactile. As I read, I imagined myself wandering the streets of Florence alongside the novel’s characters, savoring the Florentine dishes and wine, feeling the Tuscan sun on my face. Needless to say, the armchair travel this novel delivers up is divine. While I have yet see Florence, its Duomo and Uffizi, I have travelled there in a sense by reading this novel; and when someday I do make it to Tuscany, I will no doubt be thinking of Evelyn and Ulysses, Alys and Cress, Massimo and Pete and Peg.

If you love classic art and art history, enjoy a coming-of-age or family drama, are comfortable reading queer and straight romance together, and revel in books that transport you to another place, then, I imagine, this book is for you. It certainly was for me. It touchingly captures the domestic sphere of a varied cast of characters in Still Life while it highlights the many loves we humans foster over the courses of life. Still Life celebrates the incredible salve that is love.

Bibliography:

Winman, Sarah. Still Life. G. P. Putnam’s Sons: New York, 2021.

A Few Great Passages:

“‘Life’s what you make it, son,’ had been firmly entrenched in him from a young age” (18).

“It’s what we’ve always done. Left a mark on a cave, or on a page. Showing who we are, sharing our view of the world, the life we’re made to bear. Our turmoil is revealed in those painted faces—sometimes tenderly, sometimes grotesquely, but art becomes a mirror. All the symbolism and the paradox, ours to interpret. That’s how it be comes part of us. And as counterpoint to our suffering, we have beauty. We life beauty, don’t we? Something good on the eye cheers us. Does something to us on a cellular level, makes us feel alive and enriched. Beautiful art opens out eyes to the beauty of the world, Ulysses. It repositions our sign and judgement. Captures forever that which is fleeting. A meager stain in the corridors of history, that’s all we are. A little mark of scuff. One hundred and fifty years ago Napoleon breathed the same air as we do now. The battalion of time marches on. Art versus humanity is not the question, Ulysses. One doesn’t exist without the other. Art is the antidote. Is that enough to make it important? Well yes, I think it is” (26).

“Luce intellettual, piena d’amore. [. . . ] Light of the mind, full of love” (35).

“And there, a sudden clearing in the fog, as if heaven’s chenille had been pulled back just for him. Same frail finger moving across the celestial architecture. Across the constellations, and the containment and hopes of all they were. And from gambler to philosopher, he said, I’ve lived under the fickle movement of planetary adventure. I’ve encountered long dark nights when the sirens sound. But the moment stars align, and the shift of sweet wind greets you of a morning, this is when mystery becomes knowing and fortune becomes love [. . .] and the arc of flight settles a small bird a thousand miles from home with heat on its wings and a calm delight at the mastery of navigation” (55).

“There are moments in life so monumental and still that the memory can never be retrieved without a catch to the throat or an interruption to the beat of the heart. Can never be retrieved without the rumbling disquiet of how close that moment came to not having happened at all” (115).

“We’re embarking on a world of new language and new systems. A world of stares and misunderstandings and humiliations and we’ll feel every single one of them, boy. But we mustn’t let our inability to know what’ what diminish us. Because it’ll try. We have to remain curious and open. Two words for you: ley lines. [ . . .] Straight lines of electromagnetic energy crisscrossing the Earth at special sites, drawing men and women—and ideas—to their mysterious pulse. We were drawn here” (136).

“She lay down with blackbird song and wood pigeon call and bees in clover. She thoughts all of existence in this bucolic trance was a poem. Timeless, resolute, universal. The image would be repeated over the decades: women seeking solace, a safe place, bodies unclothed and held by nature” (205).

“Her mother was the knot that stopped the fraying. That’s what she learned later, and learned it the hard way, too late to say thank you truly” (223).

“She was attempting to formulate the introduction to still life painting that would include the idea of female space [. . .] The world of the domestic kitchen is a female world (she underlined this). It is a world of routine, of body and of bodily function. A world of blood and carcass and guts and servitude. Men may enter but they do not work there and yet work is all that women do there. Occasionally in such paintings, male items may appear on the table—pipes, watches, maps—often in the most ludicrous composition and yet, they succeed in what they intend to do—revoke the feminine space. Male triumph over the triviality of the scene. [ . . .] The power of still life lies precisely in this triviality. Because it is a world of reliability. Of mutuality between objects that are there, and people who are not. Paused time in ghostly absence. Who was it who prepared the food? Who gutted the fish? Who scrubbed the kitchen? These are the actions that maintain life. Objects representing ordinary life reside in this space—plates, bowls, jars, pitchers, oyster knives. The shape of these objects has remained unchanged, as has their function. They have become fixed and unremarkable in this world of habit and we have taken them for granted. Yet within these forms something powerful is retained: Continuity. Memory. Family” (238-239).

“Here would be your answered prayer. A simple image of what the moon sees: Us. A blue marbled sphere, amplified by the lunar horizon, precious and beautiful and vulnerable, floating in the eternal darkness we all shall face. [. . .] Love and love. The only ingredient required” (350).

“But one doesn’t come to Italy for niceness, one comes for life. For passion!” (403).

“A poet, you see, is a shape-shifter. [. . .] A selkie [. . .] One moment a seal, one moment a man. I am there to probe the hidden depths of the ocean—the raging tides of emotions—and then to surface in all my humanness, in all my humility, to recount in a handful of lines the myriad of tales I have encountered, the worlds in which I have traveled, the battled fought like Odysseus” (410).