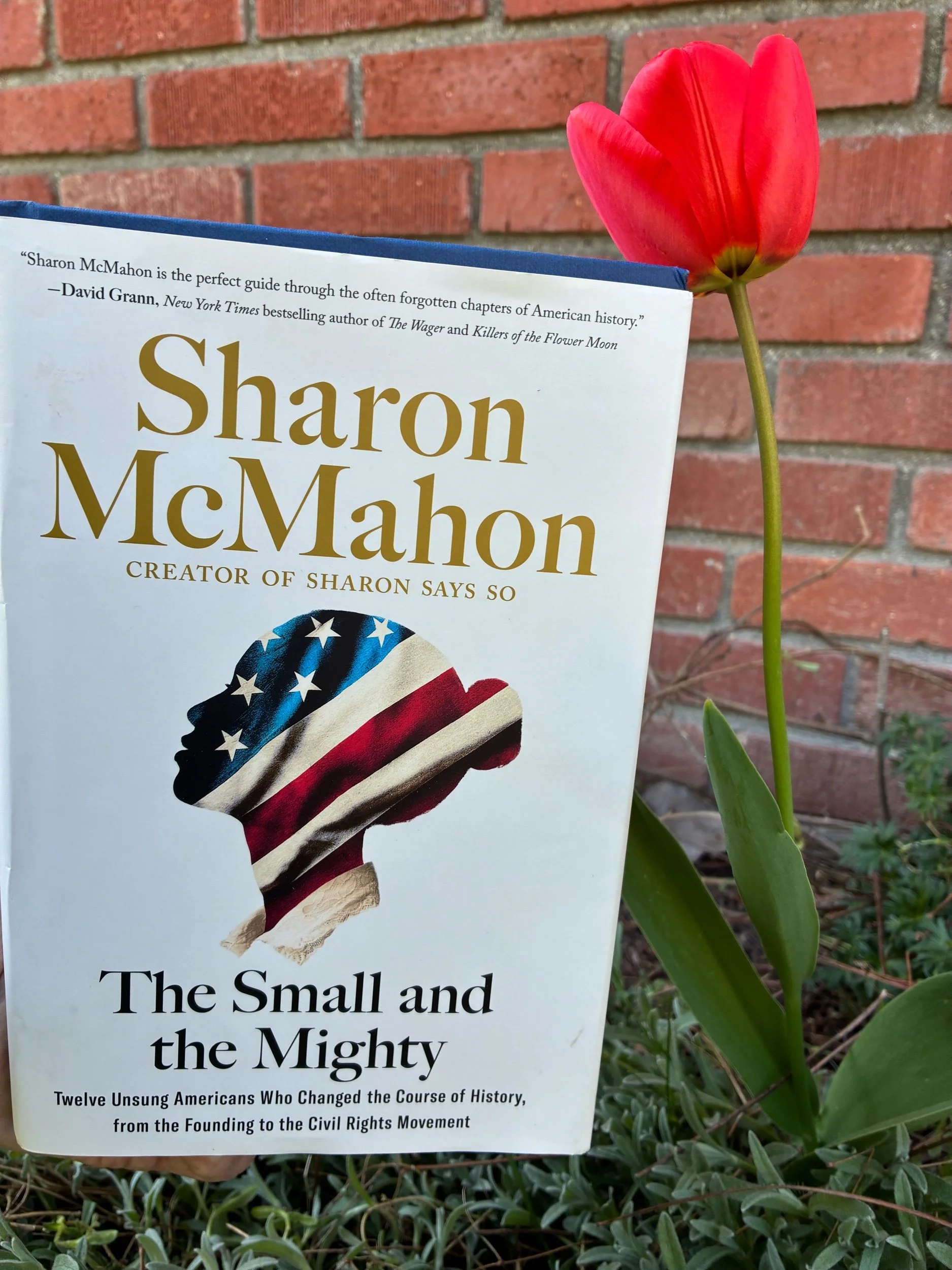

Sharon McMahon (pronounced McMan) made a name for herself as “America’s Civics Teacher” over the course of the last decade. A high school social studies teacher, she is very knowledgeable about American history and government (and the process of relaying that information to others); for years she has been sharing her passion and knowledge with anyone interested in following from her @sharonsaysso account on Instagram. She also has a very active Substack account. Last year she published her first book: The Small and the Mighty: Twelve Unsung Americans Who Changed America, from the Founding to the Civil Rights Movement (2024). The timing couldn’t have been better. This nonfiction book highlights the lives and actions of twelve Americans from our country’s inception to the Civil Rights movement who may not be well known, but whose impact was real. Indeed, The Small and the Mighty is the inspiring history lesson many of us crave of late. Its biographies capture the spirit of democracy and freedom for all that many treasure as core American values.

A few of my favorite reads…

CONTEMPORARY & CANONICAL ǁ NEW & OLD.

Fiction ※ Poetry ※ Nonfiction ※ Drama

Hi.

Welcome to LitReaderNotes, a book review blog. Find book suggestions, search for insights on a specific book, join a community of readers.