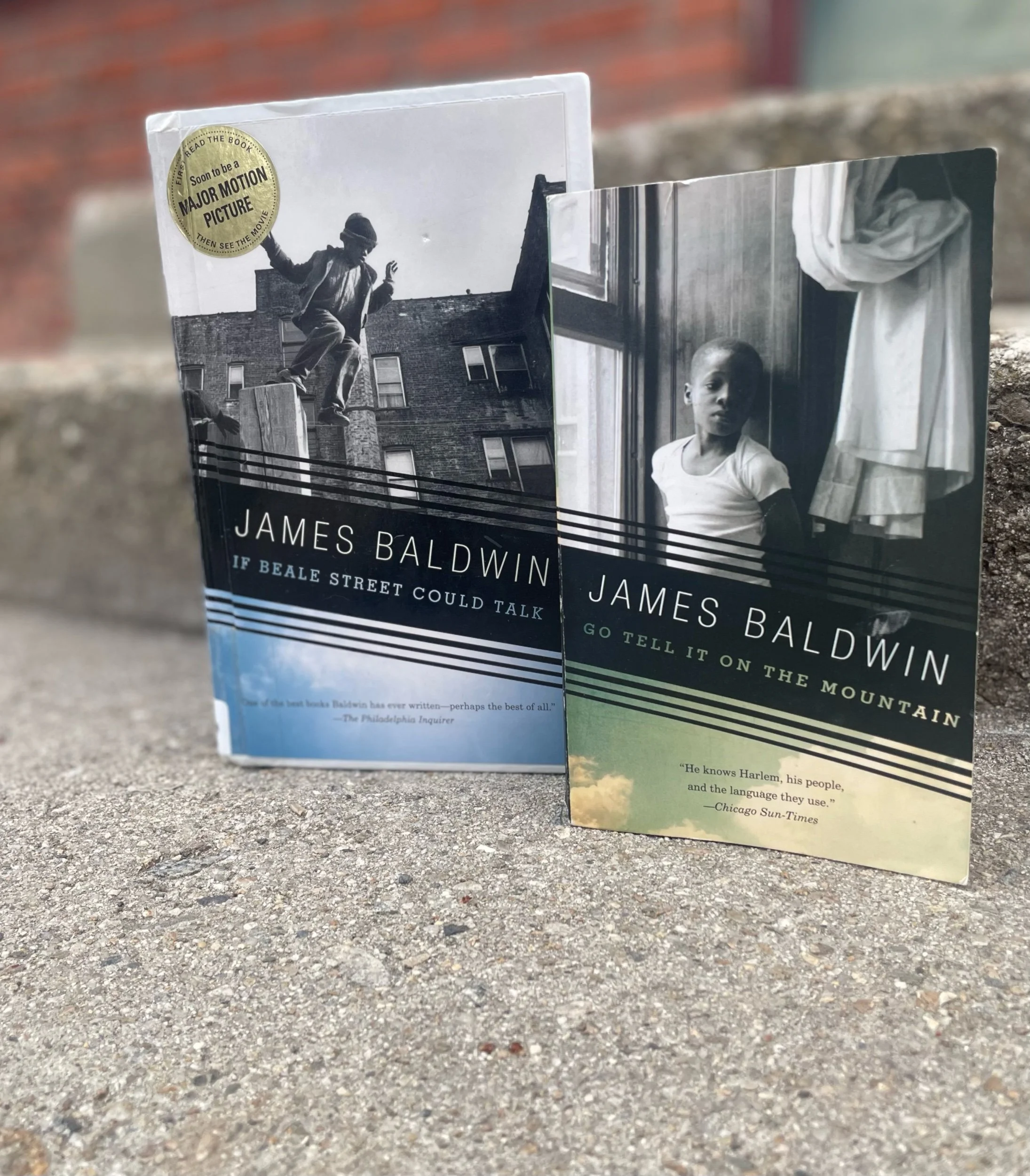

If Beale Street Could Talk & Go Tell It on the Mountain

In all his writing, James Baldwin famously gives voice to twentieth-century Black experience. His literary fiction brings the lives of everyday people to the page and their experience to the consciousness of so many people the world over; so much so he features prominently in the twentieth-century exhibit in D.C.’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. His Go Tell it on the Mountain (first published in 1954) alternates in perspective, across generations in a blended family, beginning with fourteen-year-old boy (John, loosely based on Baldwin himself). In addition to delving into issues of identity, budding sexuality, and religion, the novel paints a dynamic and very real portrait of the trauma and consequent disconnection among post-Great Migration, Black America.

Likewise, Baldwin’s If Beale Street Could Talk (1974), published twenty years later, takes readers to the New York life of its first-person heroine, Tish. From the first pages, Tish faces the heartbreak of loving a man (Fonny) wrongly imprisoned. To compound Tish’s heartache, she finds her eighteen-year-old self expecting his child. Injustice and love swirl through Tish’s life. She has the support of strong, nuclear family, albeit a poor one, and the love of a good man, even if he is incarcerated for a crime he did not commit. With the support of her older sister, mother and father, Tish bravely bears the injustice and heartache of her world. She is strong for herself, her unborn baby, and her imprisoned beloved. Set in the contemporary New York of Baldwin’s writing (1970s), from Harlem to the Village, If Beale Street Could Talk holds a mirror up for Americans to see, in Baldwin’s startling prose, voices and experiences they may not otherwise know; this novel immortalizes societal and institutional racism while also contributing a family of fiercely loyal and loving Black Americans to American literature.

Like Go Tell it on the Mountain, If Beale Street Could Talk portrays strong nuclear families among the twentieth-century Black community of New York City. Despite the hardship and inherited trauma, as well as the institutional racism they face, the individuals in both Go Tell It on the Mountain and If Beale Street Could Talk belong to families with strong bonds and authentic love. They are, however, not ideal. Both Tish and John suffer trauma because of racist institutions and histories that directly impact their lives. Indeed, it is the injustice of the system that tears Tish and Fonny’s young family apart. Likewise, the family in Go Tell It on the Mountain, struggles greatly with inherited traumas due to the generations of racist experience. It is institutional racism, rather than individual choice, that condemns the characters in both these novels to suffer.

If Beale Street Could Talk and Go Tell It on the Mountain are two of Baldwin’s most iconic books. As such, these are two books I encourage everyone to read. Through the first-person narrative of If Beale Street Could Talk and the close third of Go Tell It on the Mountain, Baldwin shares the lived experience of so many twentieth-cent Black Americans with countless readers. Indeed, books like these enable readers to strengthen their empathy and humanity by walking the pages alongside Baldwin’s resilient protagonists.

Bibliography:

Baldwin, James. If Beale Street Could Talk. Vintage International: New York, 2002.

— Go Tell It On the Mountain. Vintage International: New York, 2013.

A Few Great Passages:

“There are people in the world for whom "coming along" is a perpetual process, people who are destined never to arrive” (GTIOTM).

“But to look back from the stony plain along the road which led one to that place is not at all the same thing as walking on the road; the perspective to say the very least, changes only with the journey; only when the road has, all abruptly and treacherously, and with an absoluteness that permits no argument, turned or dropped or risen is one able to see all that one could not have seen from any other place” (GTIOTM).

“Nothing tamed or broke her, nothing touched her, neither kindness, nor scorn, nor hatred, nor love. She had never thought of prayer. It was unimaginable that she would ever bend her knees and come crawling along a dusty floor to anybody’s altar, weeping for forgiveness. Perhaps her sin was so extreme that it could not be forgiven; perhaps her pride was so great that she did not need forgiveness. She had fallen from that high estate which God had intended for men and women, and she made her fall glorious because it was so complete” (GTIOTM).

“His mind was like the sea itself: troubled, and too deep for the bravest man's descent, throwing up now and again, for the naked eye to wonder at, treasure and debris long forgotten on the bottom—bones and jewels, fantastic shells, jelly that had once been flesh, pearls that had once been eyes. And he was at the mercy of this sea, hanging there with darkness all around him.” (GTIOTM).

“And I'm not ashamed of Fonny. If anything, I'm proud.

He's a man. You can tell by the way he's taken all this shit that he's a man. Sometimes, I admit, I'm scared- because nobody can take the shit they throw on us forever. But, then, you just have to somehow fix your mind to get from one day to the next. If you think too far ahead, if you even try to think too far ahead, you'll never make it” (IBSCT 7).

“Trouble means you are alone” (IBSCT 8).

“Of course, I must say that I don't think America is God's gift to anybody-if it is, God's days have got to be numbered. That God these people say they serve-and do serve, in ways that they don't know-has got a very nasty sense of humor. Like you'd beat the shit out of Him, if He was a man. Or: if you were” (IBSCT 28).

“If you look helpless, people react to you in one way and if you look strong, or just come on strong, people react to you in another way, and, since you don't see what they see, this can be very painful” (IBSCT 46).

“That baby was our baby, it was on its way, my father's great hand on my belly held it and warmed it: in spite of all that hung above our heads, that child was promised safety. Love had sent it, spinning out of us, to us. Where that might take us, no one knew” (IBSCT 49).

“Neither love nor terror makes one blind: indifference makes one blind” (IBSCT 99).

“[I]t would take about a thousand years to try all the people in the American prisons, but the Americans are optimistic and still hope for time-and sympathetic or merely intelligent judges are as rare as snowstorms in the tropics” (IBSCT 127).