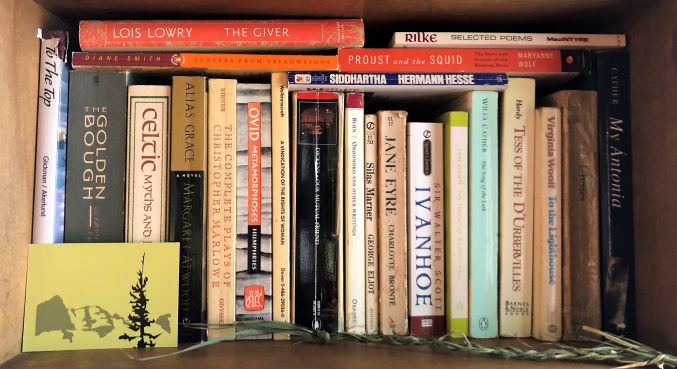

A few of my favorite reads…

CONTEMPORARY & CANONICAL ǁ NEW & OLD.

Fiction ※ Poetry ※ Nonfiction ※ Drama

Hi.

Welcome to LitReaderNotes, a book review blog. Find book suggestions, search for insights on a specific book, join a community of readers.

A few of my favorite reads…

CONTEMPORARY & CANONICAL ǁ NEW & OLD.

Fiction ※ Poetry ※ Nonfiction ※ Drama

Welcome to LitReaderNotes, a book review blog. Find book suggestions, search for insights on a specific book, join a community of readers.

All in The Classics

Siân James’s Love & War (2004) is Rhian’s story through, as the title suggests, wartime and love. The twenty-four-year-old school teacher married her high school sweetheart when he was home on leave during WWII. Despite being married for three years when the novel begins, they have only lived together fourteen days.

So often writers tease out an elaborate story by asking a series of compelling what-ifs. In the case of Percival Everett’s most recent novel, James (2024), this is certainly the case. Everett spins an alternate history of American slavery that draws the reader in and provokes readers to reconsider certain narratives. Because, what if? James is the tale of the enslaved man readers met a century ago in Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, but Everett’s Jim is far more complicated and dynamic than his literary debut (à la Twain) depicted.

Maria Dahvana Headley’s new translation of the iconic Old English poem, Beowulf (2020) presents modern readers with a perfect blend of direct translations of Old English phrases and hyperbolically contemporary verbiage. Indeed, she translate kenning (the compound word phrases frequently used in Old English poems) after kenning alongside words like “bro,” “hashtag,” and, yes, “fuck” (although the later may well have been frequently used among the warrior class of individuals depicted in Beowulf). What Headley presents is not traditional high poetry like that championed by many medievalist of yesteryear (among them the likes of Tolkien), but it is lyrical, delightfully readable, and very accessible. What’s more, it is arguably representative of the original feel of Beowulf’s oral roots. Alliterations and lyrical turns of phrase collide with 21st-century slang in Headley’s entertaining and approachable new translation of this oldest of English poems.

One of the things I love about reading books like Barbara Pym’s Excellent Women (1952) is the way the characters and language transport me to mid-20th century England—London in this case—and highlight the myriad Britishism that a Yank like me pauses and considers. Surely, we think “slut” must mean something else; as in: “‘You'd hate sharing a kitchen with me. I'm such a slut,' she said, almost proudly” (4). And, indeed it does. But the linguistic differences is just the start of what makes Excellent Women so, well, excellent. Pym’s novel emerges from the first person perspective of Mildred Lathbury, “an unmarried woman just over thirty, who lives alone and has no apparent ties” (in her own words on page 1). Her world quickly alters as Mrs. Napier moves in to the flat below her; the flat with which she shares a bathroom. Mrs. Napier and her husband, the much-anticipated Rockingham, are not what one might expect from a married couple. Excellent Women quickly populates—around the life of Miss Lathbury—with eccentric and entertaining characters. While the novel is set in London, it has a decidedly village feel and Mildred Lathbury is a wildly likable narrator.

I have certainly read thick books before, but never in such a paced manner and as January turned to February, then to March, I found myself enraptured by Tolstoy’s great work. I couldn’t believe it had taken me so long to pick it up.

Tove Jansson (1914-2001) is perhaps the most famous Finnish writer and artist of the twentieth century, but it is worth noting, she was of the Swedish speaking minority. She is best known for her Moomintroll books of animated characters that continue to charm generations of readers. Jansson also wrote crisp, flowing prose. Her slender book, The Summer Book (originally published in 1978) is a beautiful story about life on a remote island in the Gulf of Finland during the summer months.

This spring I read Wide Sargasso Sea and then re-read Jane Eyre as it had been many years since I last read Brontë’s most famous novel. Rhys’s short novel brings the Caribbean islands and Creole culture to life as it provides mad Bertha of Jane Eyre a much-needed backstory.

Valentino and Sagittarius are two novellas, both by Italian modernist, Natalia Ginzburg, translated from their original Italian. Both novellas are told in first-person, from the perspective of a young adult woman, an insignificant daughter. Both include parents with seemingly unrealistic expectations for one of the narrator’s siblings. Both come to life in post WWII Italy as they grapple with the theme of disappointment and generational divides.

Certain reads drip with comfort and charm; they transport readers in time and place to a setting that delights the senses. One such read is R. C. Sherriff’s The Fortnight in September (1931). This quintessentially British story of one family’s annual holiday (yes, in September) to the seaside town of Bognor Regis.

Virginia Woolf is a household name when it comes to lyrically figurative writing, rambling through the interior lives of characters. Her brand of modernism pairs the poetic with the complex; she champions an intellectualism that many other modernists (as well as readers and critics that have come since) have branded snobbish and off-putting. And yet, Woolf’s writing, like that of other modernists (James Joyce, for example), attempts to capture the inner life of humanity. Her fiction and nonfiction alike, excavate the uniqueness that is human thought, love, experience. In her novel To The Lighthouse (originally published in 1927 and one of my favorites among her oeuvre) Woolf again takes up this project. In this version, her investigation is Beauty (yes, with a capital “B”), the artistic process, and the muse.

Somehow it took me all these years to find my way to Zora Neale Hurston’s beautiful love story Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), but it was well worth the wait. Their Eyes Were Watching God incorporates the vernacular speech patterns of southern Blacks with poetic prose to create a powerful story.

Certain novels are slow and contemplative; they paint a portrait of a life or a time using carefully selected shades and hues to capture a mood. There may not be much action beyond that of memory, but it is enough. More than enough even. Marilynne Robinson’s winner of the Pulitzer and National Book Critics Circle Award, Gilead (2004) is one such novel. Contemplative, slow-burn writing like hers gets at the big questions of life with a hefty serving of earnest feeling sprinkled throughout. Written in first-person, Gilead is one man’s reflection upon his life, his family, and the meaning of human goodness.

Beryl Markham’s West with the Night (1942) is an eloquently written memoir that paints a series of powerful portraits of 20th-century Africa. Markham was a woman who boldly worked in male fields—race horse training and aviation—during the early- to mid-1900s. Unlike some memoir, Markham’s prose is eloquent, her imagery rich. West with the Night describes in vivid, suspenseful detail her experiences in eastern Africa, even after she left it. Among other things, this memoir reflects Markham’s love affair with Africa and the many ways that the continent formed her as a child and young adult.

This winter I enjoyed all three of L. M. Montgomery’s Emily of New Moon books: Emily of New Moon (originally published 1923), Emily Climbs (1925), and Emily’s Quest (1927). Titular character and heroine, Emily Byrd Starr, feels the call to the creative life at a young age. There is a magic tug that draws her to put pen to page. As such, her story, told over the course of this trilogy, is very much a portrait of the artist as a young woman of sorts.

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn is the story of one girl’s coming of age in the 19teens. Set, as the title suggests, in Williamsburg, Brooklyn in the first two decades of the twentieth century, this rich novel focuses on the story of Francie Nolan. It is also, however, the story of her parents and their love, her aunts and grandmother, her neighborhood at large. Ultimately this moving coming-of-age novel explores the American promise that poor American kids, the grandkids of immigrants perhaps, might realize and the magic of that promise.

After experiencing the tragedies of Boone Caudill and his companion and best friend, Jim Deakins, alongside the level-headed wisdom of Dick Summers in The Big Sky, I eagerly reached for Gutherie’s second novel, The Way West. The Big Sky had certainly impressed me, and I looked forward to reading The Way West, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, wondering how Gutherie would continue the story.

While many have certainly heard of Dickens’ other history (A Tale of Two Cities), few know his first. Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of ‘Eighty was originally published in installments throughout 1841 and it fictionalizes the very real Gordon Riots of 1780.

Set in the early twentieth-century English county side, Dodie Smith’s I Capture the Castle, is the first-person journal of Cassandra Mortmain in year of her eighteenth birthday.

John Williams’s Stoner (originally published in 1965 and re-released in 2003) follows the life of titular character William Stoner from his childhood home on the Missouri plains to the University of Missouri where he found his calling in the study literature. Williams’s prose is as plain and straightforward as is his protagonist, but the emotional depth of this novel as it weaves through decade upon decade from the 19teens onward, is deeply moving.