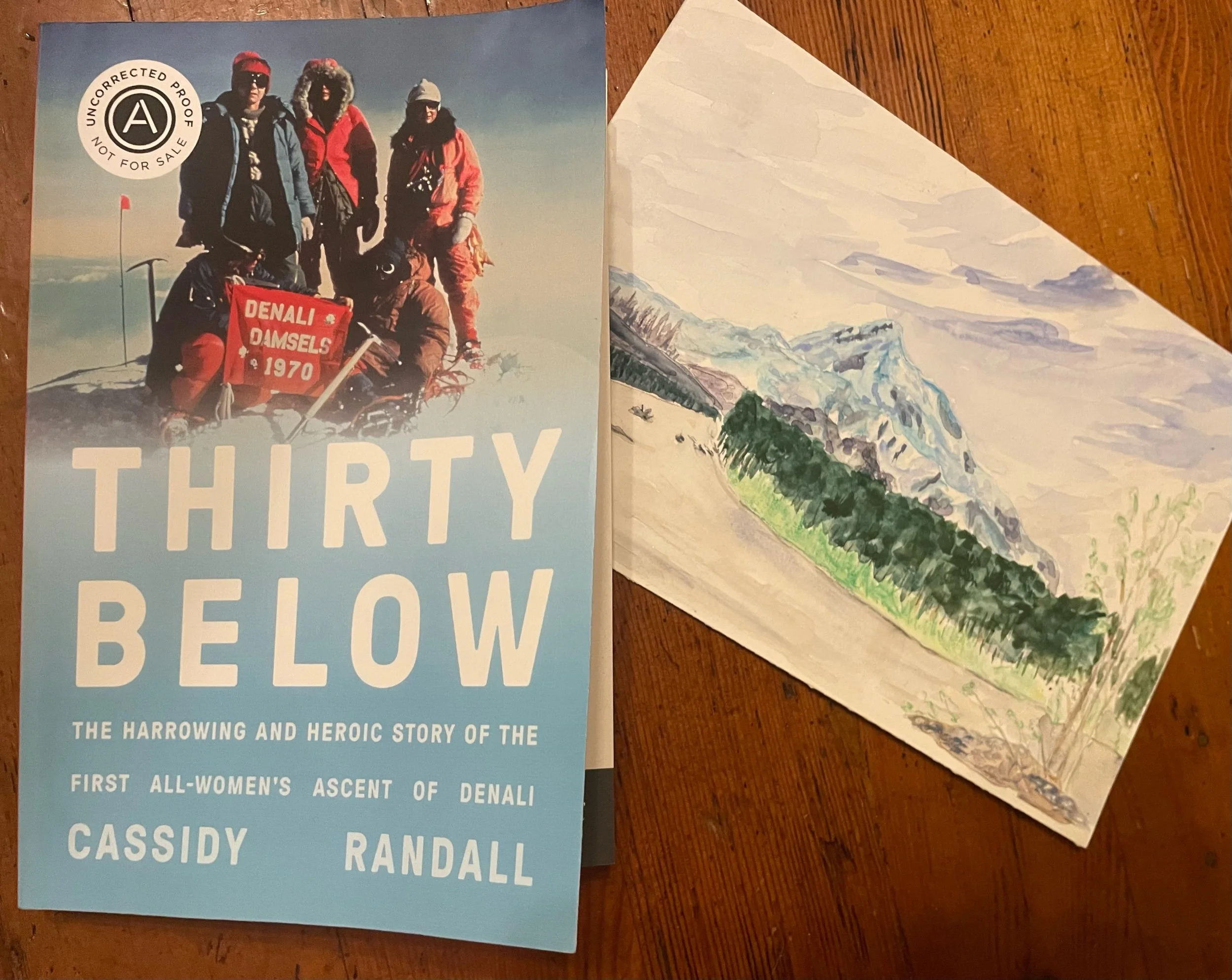

Cassidy Randall’s debut book, Thirty Below: The Harrowing and Heroic Story of the First All-women’s Ascent of Denali (2025) zooms in on a group of pioneering women mountaineers who summited the continent’s highest peak in 1970. The story takes shape as Randall introduces readers to the individual women who in time coalesce into an all-women’s climbing group. Thirty Below mixes history with carefully-researched portraits of each of the female members of the team. Ultimately, Randall creates a well-rounded biography of the individuals comprising the first all-women’s ascent of Denali alongside that of women mountaineers generally, in her brand new nonfiction, Thirty Below.

A few of my favorite reads…

CONTEMPORARY & CANONICAL ǁ NEW & OLD.

Fiction ※ Poetry ※ Nonfiction ※ Drama

Hi.

Welcome to LitReaderNotes, a book review blog. Find book suggestions, search for insights on a specific book, join a community of readers.