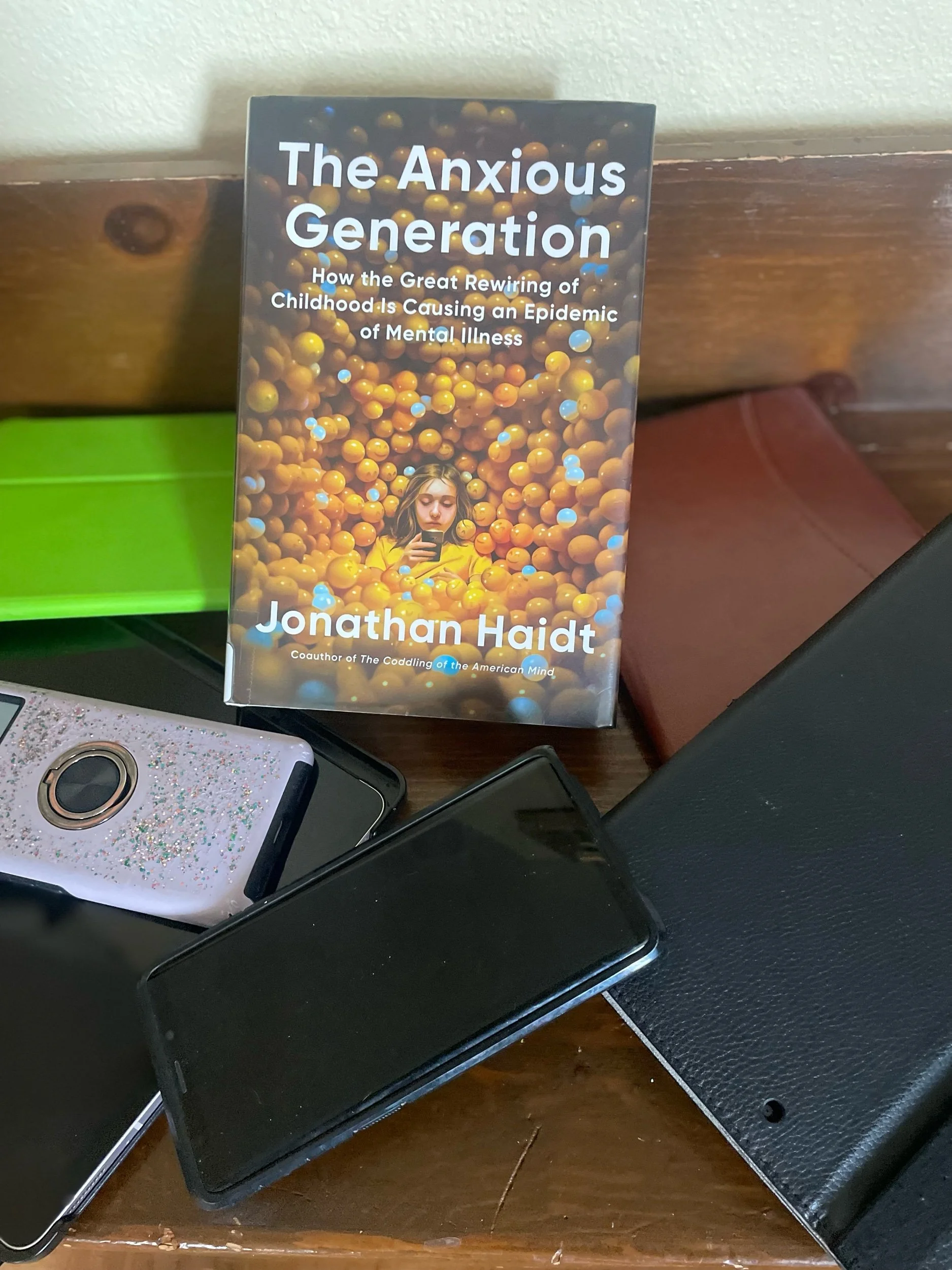

The Anxious Generation

You don’t need to be a social psychologist to recognize the social crisis of modernity. It seems particularly visible among the generation currently coming-of-age with record high levels of mental illness and increasing instances of “failure to launch.” If you happen to be a social psychologist, however, you might find yourself better equipped to unpack the underlying reasons for the generational shift. In The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness (2024), Jonathon Haidt, famous for previous books like The Righteous Mind (2012) and The Coddling of the American Mind (2018, see previous review), zooms in on the questions of why Gen Z faces such unique challenges.

The thing I particularly love about Haidt’s writing is that it always includes some hopeful opportunities for change. Some books that dissect the cultural, moral, or ethical issues of modernity tend to be doom and gloom reading, but such is not the case with Haidt’s books. Yes, there is plenty of depressing information included in The Anxious Generation as he cites stats and research that demonstrates just how anxious, isolated, and socially crippled many young people have become. Haidt defines his book as “the story of what happened to the generation born after 1995, popularly known as Gen Z, the generation that follows the millennials (born 1981 to 1995)” (5). Yet even by the end of Part Three (“The Great Rewiring”) in The Anxious Generation, Haidt begins to shift his writing away from a laundry list of symptoms and constant reference to the phone-based cause which he argues underpin all the challenges Gen Z faces; and toward something hopeful. His final chapter in Part Three (after several rather depressing chapters about what is happening to girls and boys) explores “Spiritual Elevation and Degradation.” In other words, Haidt begins to explore opportunities for growth as we foster connection to each other and the natural world, cultivate awe, and reclaim spiritual elevations whether that be through traditional religious practice or not.

From there—after citing the Buddha, Jesus Christ, the Tao Te Ching, and Marcus Aurelius alongside neuroscience—Haidt’s book fully pivots to Part Four in which he offers suggestions on “Collective Action for Healthier Childhood.” The first chapter focuses on what governments and companies can do to protect kids. He discusses things like raising the age of internet adulthood from 13 to 16, verifying ages, and government grants for phone lockers to facilitated schools being phone free, designing laws and spaces that facilitate children independence and play. In the following chapters he continues to zoom in toward the micro considering what schools can do, and then what parents can do. Thus, The Anxious Generation provides a laundry list of suggestions and considerations from the macro level of government policy down to family culture. Some of them may appear common sense to some, while they may come off as wildly radical to others. Haidt argues governments, schools, and families need to regulate children’s access to and use of phones. He is careful to point out that this also means considering parent interaction with our phones as we model how to navigate the world to our children. If the first half of The Anxious Generation left me feeling a bit hopeless, the second half does a good job at providing plenty of actionable solutions to the issues we’re all observing in the youngest adults today. While there is little doubt that some of Haidt’s assertions may not be replicable or may in time seem overstated, his general message makes plenty of sense to me. We need to protect the inquiry and discovery of childhood by limiting access to devices designed to entertain, addict, and escape. Period. Suffice it say, I highly suggest this read to anyone interested in the themes like youth, education, parenting, and technology.

NOTE: Haidt is as much an activist a he is an academic. He has founded and cofounded a number of organizations to support the changes for which he advocates: things like play-based childhoods, more robust schools, and greater autonomy given to our children. The Anxious Generation brings with its publication a robust website (anxiousgeneration.com) full of resources, updated information and stats (post publication), and more.

Bibliography:

Haidt, Jonathon. The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness. 2024)

A Few Great Passages:

“Some adults have problems with addiction to social media and other online activities, but as with tobacco, alcohol, or gambling we generally leave it up to them to make their own decisions.

The same is not true for minors. While the reward-seeking parts of the brain mature earlier, the frontal cortex-essential for self-control, delay of gratification, and resistance to temptation-is not up to full capacity until the mid-20s, and preteens are at a particularly vulnerable point in development. As they begin puberty, they are often socially insecure, easily swayed by peer pressure, and easily lured by any activity that seems to offer social validation. We don't let preteens buy tobacco or alcohol, or enter casinos. The costs of using social media, in particular, are high for adolescents, compared with adults, while the benefits are minimal” (5).

“As the transition from play-based to phone-based childhood proceeded, many children and adolescents were perfectly happy to stay indoors and play online, but in the process they lost exposure to the kinds of challenging physical and social experiences that all young mammals need to develop basic competencies, overcome innate childhood fears, and prepare to rely less on their parents. Virtual interactions with peers do not fully compensate for these experiential losses” (8).

“It is in unsupervised, child-led play where children best learn to tolerate bruises, handle their emotions, read other children's emotions, take turns, resolve conflicts, and play fair” (53).

“Maybe it's because it's not healthy for any human being to have unfettered access to everything, everywhere, all the time, for free” (194).

“I'll draw on wisdom from ancient traditions and modern psychology to try to make sense of how the phone-based life affects people spiritually by blocking or counteracting six spiritual practices: shared sacredness; embodiment; stillness, silence, and focus; self-transcendence; being slow to anger, quick to forgive; and finding awe in nature” (202).

“Humans evolved in nature. Our sense of beauty evolved to attract us to environments in which our ancestors thrived, such as grasslands with trees and water, where herbivores are plentiful, or the ocean's edge, with its rich marine resources. The great evolutionary biologist E. O. Wilson said that humans are ‘biophilic,’ by which he meant that humans have ‘the urge to affiliate with other forms of life.' This is why people travel to wondrous natural destinations. It's why the great landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted designed Central Park the way it is, with fields, woods, lakes, and a small zoo where my children delighted in feeding sheep and goats. It's why children love to explore the woods and turn over rocks, to see what they'll find crawling underneath. This is also why spending time in beautiful natural settings reduces anxiety in those suffering from anxiety disorders.’ It's like coming back home” (214).

“If we want children to meet each other face-to-face and interact with the real world—not just screens—the world and its inhabitants have to be accessible to them. A world designed for automobiles is often not one that children find accessible. Cities and towns can do more to be sure that they have good sidewalks, crosswalks, and traffic lights. They can install traffic calming measures, and they can change their zoning to allow more mixed-use development. When commercial, recreational, and residential establishments are more mashed up together, there is more activity on the street and more places that children can get to on foot or by bike. But when the only way for a kid to get to a shop, park, or friend's house is by ‘parent taxi,’ more kids will end up at home on a screen. One study found that kids who can get to a playground by bike or foot are six times more likely to visit it than kids who need someone to drive them. So scatter playgrounds throughout a neighborhood, and consider having a few of them be adventure playgrounds” (242).

“The evidence that phones in pockets interfere with learning is now so clear that in August 2023, UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization) issued a report that addressed the adverse effects that digital technologies, and phones in particular, are having on education around the world? The report acknowledged benefits of the internet for online education and educating some hard-to-reach populations, but noted that there is surprisingly little evidence that digital technologies enhance learning in the typical classroom. The report also noted that mobile phone use was associated with reduced educational performance and increased classroom disruption. So going phone-free is a crucial first step. Each school would still need to consider the effects of laptops, Chromebooks, tablets, and other devices through which students can text each other, access the internet, and be pulled away into digital distractions. The value of phone-free and even screen-free education can be seen in the choices that many tech executives make about the schools to which they send their own children, such as the Waldorf School of the Peninsula, where all digital devices-phones, lap-tops, tablets-are prohibited. This is in stark contrast with many public schools that are advancing 1:1 technology programs, trying to give every child their own device.' Waldorf is probably right” (249-250).

“Additional evidence that phones may be interfering with education in the United States can be found in the 2023 National Assessment of Educational Progress (otherwise known as the nation's report card), which showed substantial drops in test scores during the COVID era, erasing many years of gains. However, if you look closely at the data, it becomes clear that the decline in test scores began earlier. Scores had been rising pretty consistently from the 1970s until 2012, and then they reversed. COVID restrictions and remote schooling added to the decline, especially in math, but the drop between 2012 and the beginning of COVID was substantial. The reversal coincided with the moment teens traded in their basic phones for smartphones, leading to a big increase in attention fragmentation throughout the school day. But it wasn't Kurt Vonnegut's egalitarian dystopia, where the top students had to wear an earpiece that disrupted their thoughts. Instead, it was the students in the lower quarter whose scores dropped the most between 2012 and 2020. These students are disproportionately from lower-income households, with Black and Latino students overrepresented.

Studies show that lower-income, Black, and Latino children put in more screen time and have less supervision of their electronic lives, on average, than children from wealthy families and white families. (Across the board, children in single-parent households have more unsupervised screentime.) This suggests that smartphones are exacerbating educational inequality by both social class and race. The ‘digital divide’ is no” (250) ‘longer that poor kids and racial minorities have less access to the internet, as was reality in the early 2000s now that they have less protection from it’” (251).

“Risking a serious injury for no good reason is dumb. But some risk is part of any hero's journey, and there's plenty of risk in not taking the journey too” (284).

“Until someone finds a chemical that was released in the early 2010s into the drinking water or food supply of North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand, a chemical that affects adolescent girls most, and that has little effect on the mental health of people over 30, the Great Rewiring is the leading theory” (290).

“Each school that goes truly phone-free liberates all of its students to be more present with each other” (290).