Galatea

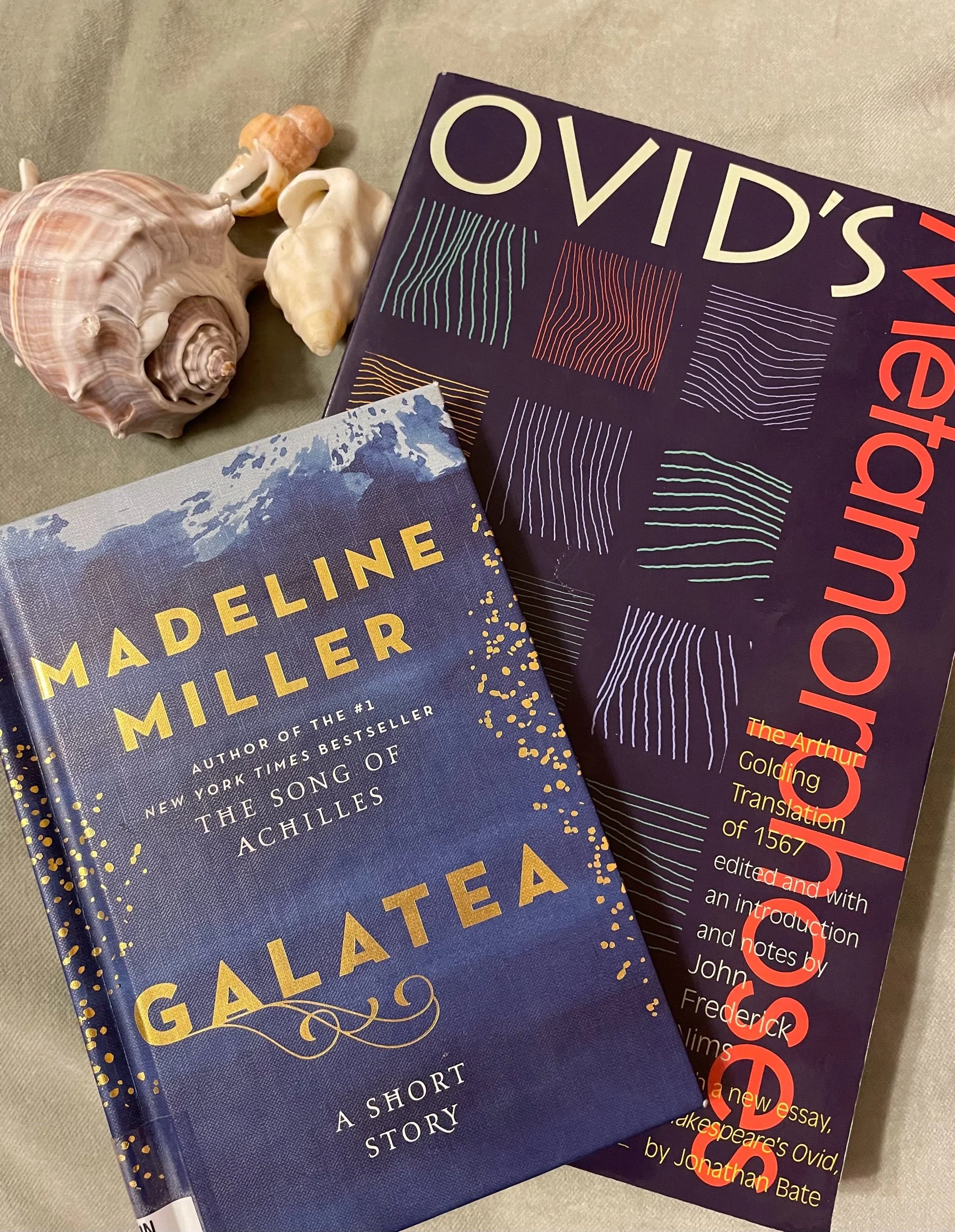

Madeline Miller’s short work, Galatea (originally published 2013), is a satisfyingly tiny book. Bound in hardcover with petite dimensions (roughly 4” x 6”), this little book is only 56 pages (including a six-page afterword). The story itself, like Miller’s novel-length Circe (previously reviewed—the first on LitReaderNotes— here) and The Song of Achilles (previously reviewed here), is a feminist retelling of classical myth. Miller fleshes out Galatea’s story from the story of Pygmalion in Ovid’s Metamorphosis. Pygmalion, readers may recall, is the gifted sculptor who forms the ideal woman from ivory stone. She is beautiful and silent as he caresses her alabaster form. Pygmalion dresses and undresses the sculpture; he even brings her to his bed. His lustful love leads him to pray to Venus for assistance. Like the trouble-making goddess that she is, Venus transforms the nameless maiden of Pygmalion’s sculpture to fertile flesh. Nine moons hence, Pygmalion and his sculpture-turned-wife welcome a child into their home. Miller picks up their story when that child (male in Ovid, female in Miller’s telling), Paphos, is ten.

Miller’s Galatea gives voice and boldness of self-determination to perhaps the greatest portrayal of feminine objectification a name, in this revision of classical myth. Ovid’s story does not name Pygmalion’s sculpture turned wide. Rather, the name Galatea (meaning milky white) originates with 18th-century Rousseau. Indeed, Ovid’s version focuses on Pygamlion’s obsession, Venus’s intercession, and the tragedy inherited by their grandson who is King Cinyras father of incestuous Myrrah (their story follows Pygmalion’s in Metamorphosis. In Ovid’s understated, subtle way then, readers might take Pygmalion’s story as a cautionary tale. Yet, modernity has transformed this troubling, arguably misogynistic story of an artist enamored with his art, into a love story. Perhaps most famous of these is George Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion (originally staged in German in 1913 and in English in 1914, revised in 1941) about Professor Higgins and Elizabeth Doolittle (yes, inspiration for the musical My Fair Lady). Yet, Shaw refused to give his audience the happy ending of Eliza marrying Higgins (the ending they find in the famous My Fair Lady). In response to directors wishing to shift the ending to make it a happily ever after story, Shaw wrote an essay titled “What Happened Afterwards” in 1916 that insisted that Eliza must leave Higgins in order to live. To all this, Miller’s Galatea responds with Galatea’s voice and life, confined and terrifying as it may be. Notably in Miller’s version, the sculptor/husband, the famous Pygmalion, remains nameless.

In Galatea readers find classical myth colliding with a sort of “The Yellow Wallpaper” (originally published in 1892). Like in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s short story, Miller’s emerges in first-person perspective, narrated by a wife who has been locked away by her husband in the name of her health. In both cases, the female narrators both exist in a manner and place according to their husbands’ wishes. They both suffer for lack of freedom and self determination. They both have one child. They both exist, confined to a room high off the ground, confined in the name of medicine. And yet, unlike Gilman’s heroine, Miller’s Galatea resists her confinement; she does not succumb to madness. While Gilman’s protagonist resists through the pen, Miller’s acts deliberately and sculpts her own ending for her story.

Thus, readers find in Miller’s Galatea a feminist response to the disturbing story of Pygmalion. Anyone who enjoys a good feminist reboot to an old story will enjoy this short story which Miller calls the little sister to her novel-length works (51). If you do find your way to this tiny book, be sure to read Miller’s afterword after finishing the story itself. It is a compelling work of feminist literary criticism as well as a reflection of her writer’s craft in penning Galatea.

Bibliography:

Miller, Madeline. Galatea. Ecco: 2022.

Ovid. Metamorphosis. Trans. by Arthur Golding in 1567. Paul Dry Books: 2000.

Perkins Gilman, Charlotte. “The Yellow Wallpaper.” Project Gutenberg: The Yellow Wallpaper | Project Gutenberg

“Pygmalion (play)” Wikipedia. Pygmalion (play) - Wikipedia

A Few Great Passages:

“[I]t does seem foolish that he didn't think it through, how I could not both live and still be a statue. I have only been born for eleven years, and even I know that” (24).