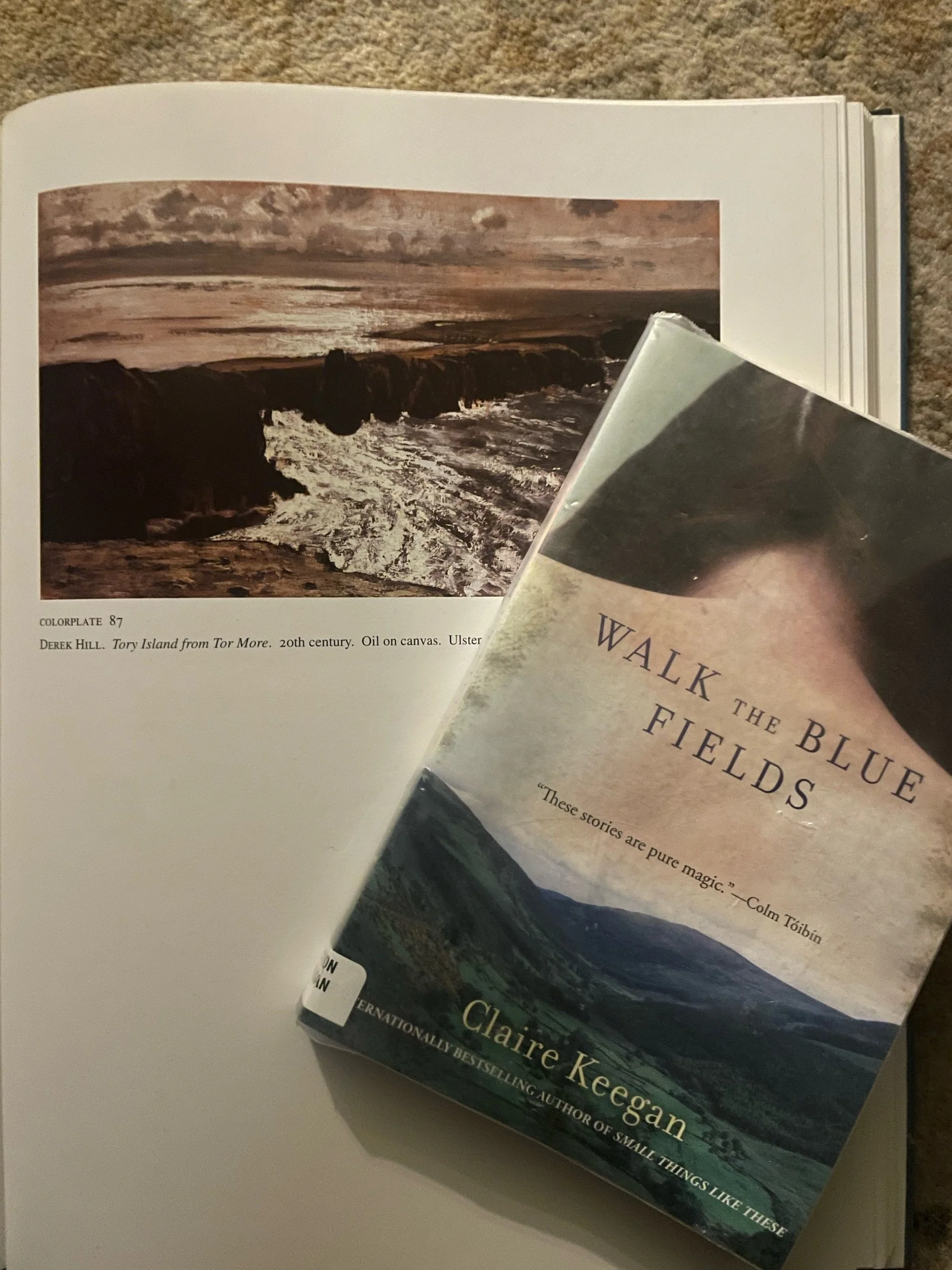

Walk the Blue Fields

Claire Keegan’s collection of seven short stories, Walk The Blue Fields (2007), is everything fans of her Small Things Like These (previously reviewed here), Foster, and So Late in the Day (previously reviewed here) will expect. Her prose is somehow both sparse and lyrical. Her characters are dynamic despite scant description. In the course of few pages, Keegan’s stories unravel and leave the reader breathless and teary-eyed. Each story creates a momentary snapshot of Ireland, one of millions of snapshots a curious observer might find on any given day. The stories take little time to read but they linger; they annoy and provoke; they glisten like morning dew on the grass, an image that remains long after it evaporates with the day.

In the first story of the collection, “The Parting Gift,” the narrative unfolds in second person. Keegan places the reader in the desperate experience of its heroine: the youngest daughter shrouded in shame. Sent by her mother, for years, the girl has replaced the mother in her father’s bed. But this is the moment of parting as the girl embarks for New York. We know little beyond the gentle care of an older brother and the power of a locked door. Like many of Keegan’s short stories, “The Parting Gift” will turn the reader’s gut, call mist to one’s eye, and demand to be seen.

The titular story, “Walk the Blue Fields,” begins with an Irish country wedding. As one expects in Keegan’s stories, something is amiss, but the ceremony goes off without event. Afterwards, the priest, followed closely by the story’s third person perspective, turns to town and the reception rather than the field through which he likes to walk. Through the reception and the priest’s subsequent walk, the reader observes him sorting out love and coming to understand where God is. Following the priest’s inner thoughts, the reader joins the priest as he finds the peace walking the blue fields. Away from the village, he finds healing in unlikely hands and the day ends with quiet epiphany.

“The Forester's Daughter” is Martha’s story of the life in which she finds herself married to respectable farmer, Victor Deegan. A hunting dog, Judge, the hens and the roses, and their three children, the youngest of whom is Victoria, round out the family in time. At the heart of Martha’s tale is an act of storytelling that upends a family.

Other stories include “The Long and Painful Death” also included in the more recent collection: So Late in the Day (previously reviewed) and “Surrender (after McGahern)” about the IRA. The collection concludes with the folklore-rich “Night of the Quicken Trees,” which conflates a contemporary Irish village life with fairytale. Magic courses just below the surface in this tale of heart break and redemption.

Walk the Blue Fields is the last of Claire Keegan’s published works that I have read. Now that I have read all that she has published (to my knowledge), I can unequivocally state that she is a master storyteller; anyone who appreciates a good yarn or the Irish way, will undoubtedly be—like me—a dedicated fan of her writing. It is also exciting that her most known work, Small Things Like These, was adapted last year into a film with Cillian Murphy among others. With a 93% Rotten Tomatoes score, and its source material in Keegan, it is sure to be a wonderful (and heartbreaking) film.

Bibliography:

Keegan, Claire. Walk the Blue Fields. Black Cat: New York. 2007.

A Few Great Passages:

“Now, the priest stands outside and stares at the chapel grounds. It is a fresh day, bright with wind. Confetti has blown across the tombstones, the paving, up the graveyard path. On the yew, a scrap of veil quivers. He reaches up and takes it from the branch. It feels stiff in his hand, stranger than cloth” (WTBF, 17).

“On either side, the trees are tall and here the wind is strangely human. A tender speech is combing through the willows. In a bare whisper, the elms lean. Something about the place conjures up the ancient past: the hound, the spear, the spinning wheel. There's pleasure to be had in history. What's recent is another matter and painful to recall” (WTBF, 18).

“It's what she once wanted but two people hardly ever want the same thing at any given point in life. It is sometimes the hardest part of being human” (WTBF, 31).

“She said self-knowledge lay at the far side of speech. The purpose of conversation was to find out what, to some extent, you already knew. She believed that in every conversation, an invisible bowl existed. Talk was the art of placing decent words into the bowl and taking others out. In a loving con-versation, you discovered yourself in the kindest possible way, and at the end the bowl was, once again, empty” (36).

“Seldom did neighbours come into that house but whe ever they did, Martha told stories. In fact, she was at be best with stories. On those rare nights they saw het phot things out of the air and break them open before their eyes They would leave remembering not the fine old house the always impressed them or the man with the worried lock that owned it or the strange flock of teenagers but the woman with the dark brown hair which got looser as the night went on and her pale hands plucking unlikely sto ries like green plums that ripened with the telling at her hearth” (Fd, 56).

“Deegan is now middle-aged. If it is a stage when some believe that much of life is over, and assume that what's left is a downhill slope to be lived within the restraints of choices made, for Deegan, it is otherwise” (Fd, 57).

“Judge is glad he cannot speak. He has never understood the human compulsion for conversation: people, when they speak, say useless things that seldom if ever improve their lives. Their words make them sad. Why can't they stop talking and embrace each other?” (FD, 64-65).

“He would like sometimes to carry her away from this place and tell her what is on his mind and start all over again” (67).

“Martha concentrates on the room. She has a way about her that is sometimes frightening. She looks at her feet and concentrates. Before she can begin she must find the scent; every story has its own, particular scent. She settles on the roses” (79).

“It was the easiest thing in the world to humiliate some-body. He had said this aloud at his wife's side in bed one night, in the darkness, thinking she was asleep, but she had answered back, saying it was sometimes harder not to humiliate someone, that it was a weakness people had a Christian duty to resist. He had stayed awake pondering the statement long after her breathing changed. What did it mean? Women's minds were made of glass: so clear and yet their thoughts broke easily, yielding to other glassy thoughts that were even harder. It was enough to attract a man and frighten him all at once” (S, 115).