Circe: A Novel

In this 2018 novel (published by Little, Brown & Co.) Madeline Miller brings the goddess, Circe, to life. Miller tells the story of Circe’s youth in poetic detail, her days spent in the halls of the Titan ever the outcast, the witch. As Circe matures her journey takes her to the land of the mortals with visits from the occasional Olympian. Thus her inner struggles, woes, and desires construct the novel’s narrative as Miller presents a dynamic portrayal of Circe’s life as an immortal.

In this beautiful re-weaving of Circe’s stories, Miller expertly adorns many classical tales with plenty of her own invention. This novel consumes the reader and I found it hard to walk away from the classical imagery, the ancient stories, until I had completed the final sentence. Miller forms a narrative that is at its core vulnerable, human, hopeful, and life affirming; she skillfully does so through the life and voice of the titular goddess.

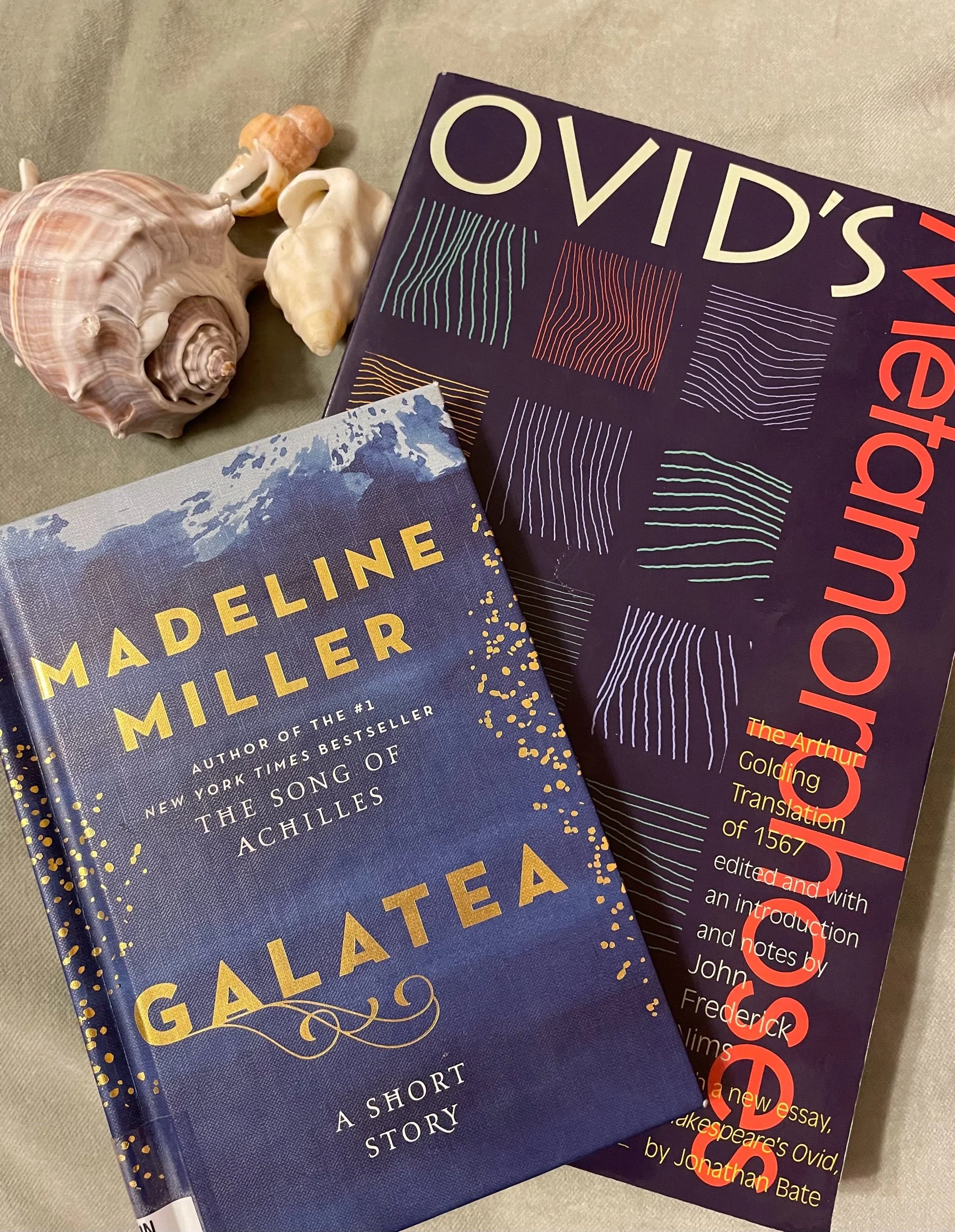

This is a book any lover of Greek myth and classical antiquity should pick up. As I completed its final passages, I reached for my copy of The Odyssey to remind myself how Homer had described this enigmatic character. In the classical texts we readers rarely glimpse the interior life of immortals. It is out of this vacuum that Madeline Miller derives her subjects. If, you do read (and love) Circe as I did, I also encourage you to find a copy of her older novel—also a retelling of a famous classical story—The Song of Achilles.

“ Miller forms a narrative that is at its core vulnerable, human, hopeful and life affirming; she skillfully does so through the life and voice of the titular goddess.”

A Few Great Passages:

“A thousand years I had lived, but they did not feel so long as Telegonus’ childhood I prayed that he would speak early, but then I was sorry for it, since it only gave voice to his storms. No, no, no he cried, wrenching away from me. And then, a moment later, he would climb over my lap, shouting Mother until my ears ached. I am here, I told him, right here. Yet it was not close enough. I might walk with him all day, play every game he asked for, but if my attention strayed for even a moment, he would rage and wail, clinging to me. I yearned for my nymphs then, for anyone that I might seize by the arm and say, What is wrong with him? But then in the next moment, I was glad no one could see what I had done to him, letting all those early months of my terror batter at his head. No wonder he stormed” (259).

“‘Life is not so simple as a loom. What you weave, you cannot unravel with a tug’” (in the words of Penelope, 346).

“I know how lucky I am, stupid with luck, crammed with it, stumbling drunk. I wake sometimes in the dark terrified by my life’s precariousness, its thread breath. Beside me, my husband’s pulse beats at his throat; in their beds, my children’s skin shows every faintest scratch. A breeze would blow them over, and the world is filled with more than breezes: diseases and disasters, monsters and pain in a thousand variations” (384).