Tom Lake

Ann Patchett’s Tom Lake (2023) is a slight novel (page count just over 300) that explores storytelling and story-receiving, innocence and experience, memory and truth. Set during the long, slow days of pandemic lockdown, Tom Lake follows a mother unwinding the tale of her youth to her now young adult daughters. Lara (née Laura) recounts her youth (it begins when she is weeks away from the close of her junior year of high school) and her unexpected early success as an actress. In other words, it is a coming of age novel told first-hand but with the distance and maturity of many years that interweaves its narrator’s interior thoughts, revealing more than what is told. As she tells the story, Lara must face not only memory but also her daughters’ interruptions, her husband’s occasional comments, and her own ghosts. Their interjections constantly push her toward one end, but her story, she insists, is bigger. Just as the novelist makes choices about what to tell, when and how, Lara attempts to craft her story until it becomes a thing of its own. Tom Lake, then, delightfully highlights the very act of storytelling and like a set of Russian dolls, stories live concealed within others to the final pages.

Beginning with the novel’s dedication page (“For Kate DiCamillo who held the lantern high”), Tom Lake suggests we tell our children truth. Just as DiCamillo boldly shares stories about the loss and darkness intrinsic to human experience (and our audacious ability to persevere) with young people in her novels, Patchett’s novel models an openness we should strive for with our children, even if we don’t include all the details. Indeed, it seems a subtle imperative: share your stories; your children want to know. In some cases, as with Lara’s eldest daughter, they need to know. Storytelling, Tom Lake reminds us, is a personal act and one that brings us closer to one another and ourselves.

Patchett’s heroine traipses trough memory in gentle stream of consciousness, looking back on and the complexity of retelling youthful experiences to one’s adult children. There exists in Tom Lake, just as surely as in maternity, the multilayered vision any mother has of her children: they are their current age and also they are all the ages that came before. As such, the relationship is wildly complex. To further complicate it, a child can never really know her parent’s experience in full. Even after three-hundred pages of story sharing, Lara’s daughters only know one version of events. Despite considerable sharing on their mother’s part, the daughters will never know the whole story (as we readers will). This is a fundamental truth about people: we can’t read other people’s interior monologues as we do in novels, we can only know them from what we witness and what they reveal. This is as true for strangers passed on the street as it is for our own loved ones.

In addition to the complexities involved in a mother recounting a steamy summer she experienced when she was the age her daughters are now, troubling and comical as those complexities may be, Patchett’s novel also touches on contemporary life and language. Tom Lake captures pandemic experience naturally and in understated tones. Readers can wrap up in it like a well-worn, familiar quilt, despite its stains and threadbare patches. Likewise, it reflects the hypersensitivity of cancel culture at its zenith. There is a tragic-comedy that plays out as Lara’s daughters school her on what she can and cannot say in today’s milieu. Patchett nails a historical moment here and reflects the gags we place on one another for fear of being perceived as insensitive. At one point, Lara responds to such an interruption with the very real: “I’m not sure how much of a story is going to be left” (136). And with that simple line Patchett’s novel provides a gentle response to our exaggerated fear of what can and cannot be told. Yet, she also reflects the power of its sentiments. One daughter responds, “Maybe you should just tell us what happened [. . .] just the facts, without attaching an judgement” (137) so Lara does, and wow. Powerful storytelling unfolds. Patchett manages to capture the complexity of our cultural mores, the feelings of absurdity and the power of telling without judgement, in one short scene. Brilliant.

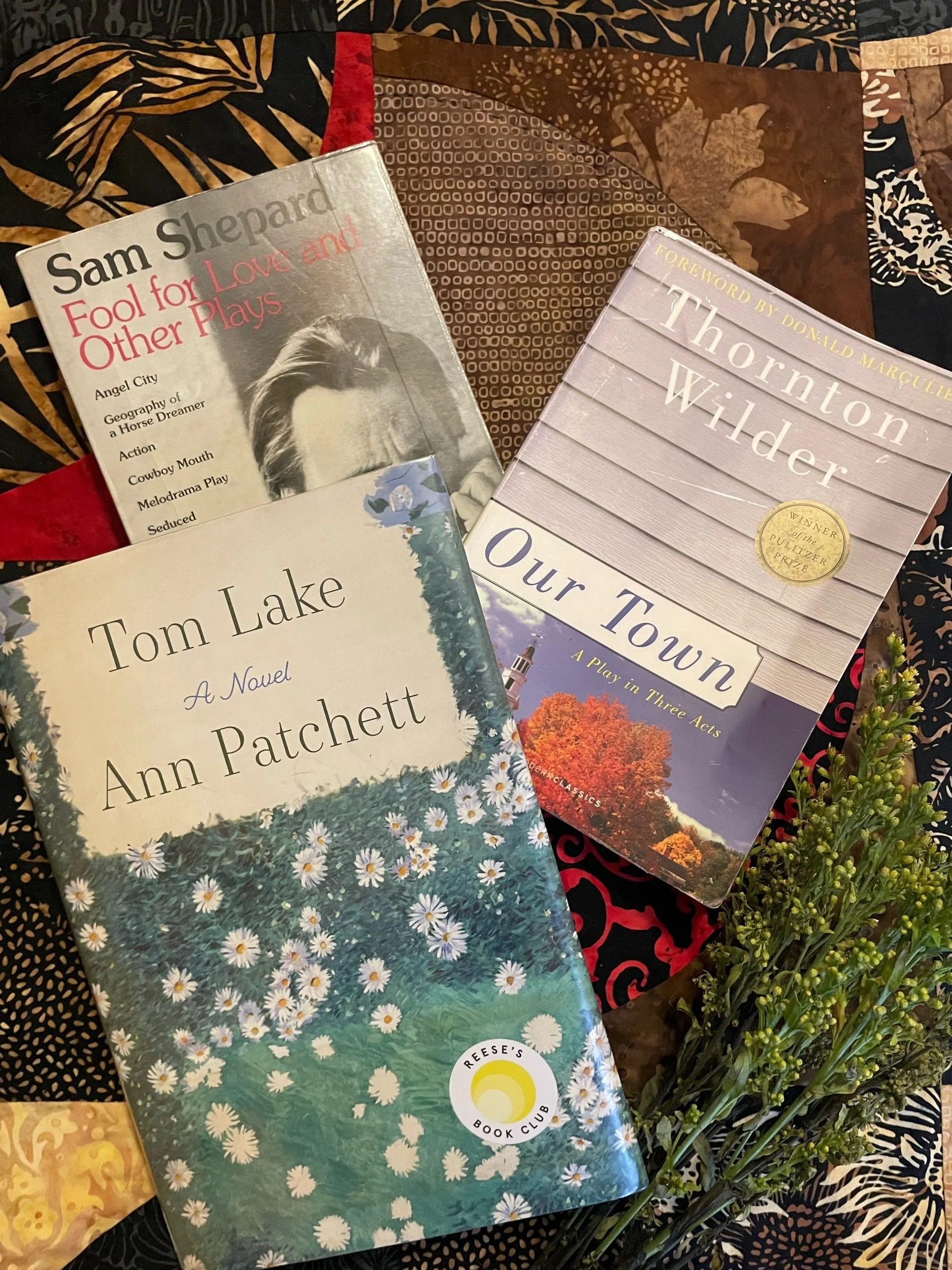

Tom Lake is a story nested within stories: a youthful love affair told from a distance of time and maturity; a novel nested within several plays. Indeed, Thornton Wilder’s Our Town (first staged in 1938)* and Sam Shepard’s Fool for Love (first performed in 1983) book end Lara’s tale and add narrative depth. These plays are classic American stage drama that both include themes of innocence and experience. Framing Lara’s summer of love and betrayal is a domestic drama that reflects many of the current moment’s issues. It takes readers back to the psychology of pandemic: those long days of isolation but also family togetherness. It reflects Gen Z generational responses to love, justice, and climate change, and how they differ so much from the choices of their Gen X parents. Patchett brilliantly interweaves a young woman’s coming of age, narrated by herself roughly thirty years later and addressed to her daughters, with the domestic realities of watching one’s children step fully into adulthood. Indeed, Tom Lake is a beautiful tribute to the joy of mothering daughters and the aging process. The parallels (and contrasts) between their mother’s long-ago tale and her daughters’ own youthful experiences provide a symmetry to the two narrative threads; they reflect the nature of life’s circular nature and the way we return to our youth as we watch our children live their own.

* Wilder’s play, in particular, is a joy to read and well worth the side trip. Patchett implores her readers to do so in her author’s note at the close of Tom Lake. She describes the play as “an enduring comfort, guide, and inspiration throughout my life” (309). Patchett goes on to suggest that “turn[ing] the reader back to Our Town, and to all of Wilder’s work” is her novel’s “goal” (309). My heart sings when literature points readers to other literature. It seems, so too, does Patchett’s; she concludes the short entreaty: “Therein lies the joy” (309). Patchett does not exaggerate the beauty and impact of Our Town. (I’ve included a few great passages from the play below to illustrate its power.) It is a short play and can be read in a sitting. I reiterate Patchett’s gentle suggestion, strengthen it to an imperative, in fact: go, read Our Town. It is accessible and wonderfully American. Shepard’s Fool for Love is powerful too, but not “an enduring comfort.” Rather, it centers on lust and sexual love, as well as the relentlessness, desperation, and filth of modernity.

Bibliography:

Patchett, Ann. Tom Lake. Harper: 2023.

Shepard, Sam. Fool for Love and Other Plays. Dial Press Trade Paperbacks: 1984.

Wilder, Thorton. Our Town: A Play in Three Acts. Harper Perennial Modern classics : 2003.

A Few Great Passages:

“‘You remember it that way because it makes a better story[. . .] That doesn't means it's true’” (Patchett, 20).

"’I'm starting to understand something here,’ she says, and all of us think she's talking about the tree.

‘Every thing leads to the next thing.’

Maisie stops to look at her sister. ‘That's called narrative. I guess they don't teach you that in hort [horticulture] school.’

‘I understand narrative, idiot, but when you see it all broken down this way, step by step, I don't know, it's different’” (61).

“This sorrow at the thought of exclusion you wish to protect your dear father from, that's what I've been feeling all morning. But I have been here long enough to understand the difference between daughters and mothers and daughters and fathers. We promise to wait. Secrets are at times a necessary tool for peace” (105).

“There is no explaining this simple truth about life: you will forget much of it. The painful things you were certain you'd never be able to let go? Now you're not entirely sure when they happened, while the thrilling parts, the heart-stopping joys, splintered and scattered and became something else. Memories are then replaced by different joys and larger sorrows, and unbelievably, those things get knocked aside as well, until one morning you're picking cherries with your three grown daughters and your husband goes by on the Gator and you are positive that this is all you've ever wanted in the world” (116).

“I look at my girls, my brilliant young women. I want them to think I was better than I was, and I want to tell them the truth in case the truth will be useful. Those two desires do not neatly coexist, but this is where we are in the story” (240).

“The past, were I to type it up, would look like a disaster, but regardless of how it ended we all had many good days. In that sense the past is much like the present because the present—this unparalleled disaster is the happiest time of my life” (253).

“I guess we're all hunting like everybody else for a way the diligent and sensible can rise to the top and the lazy and quarrelsome can sink to the bottom. But it ain't casy to find. Meanwhile, we do all we can to help those that can't help themselves and those that can we leave alone” (Wilder, 25-26).

“Now there are some things we all know, but we don't take m out and look at'm very often. We all know that something is eternal. And it ain't houses and it ain't names, and it ain't earth, and it ain't even the stars... everybody knows in their bones that something is eternal, and that something has to do with human beings. All the greatest people ever lived have been telling us that for five thousand years and yet you'd be surprised how people are always losing hold of it. There's something way down deep that's eternal about every human being” (Wilder, 87-88).

“Oh, earth, you’re too wonderful for anybody to realize you [. . . ] Do any human beings ever realize life while they live it? — every, every minute?” (Wilder, 108).