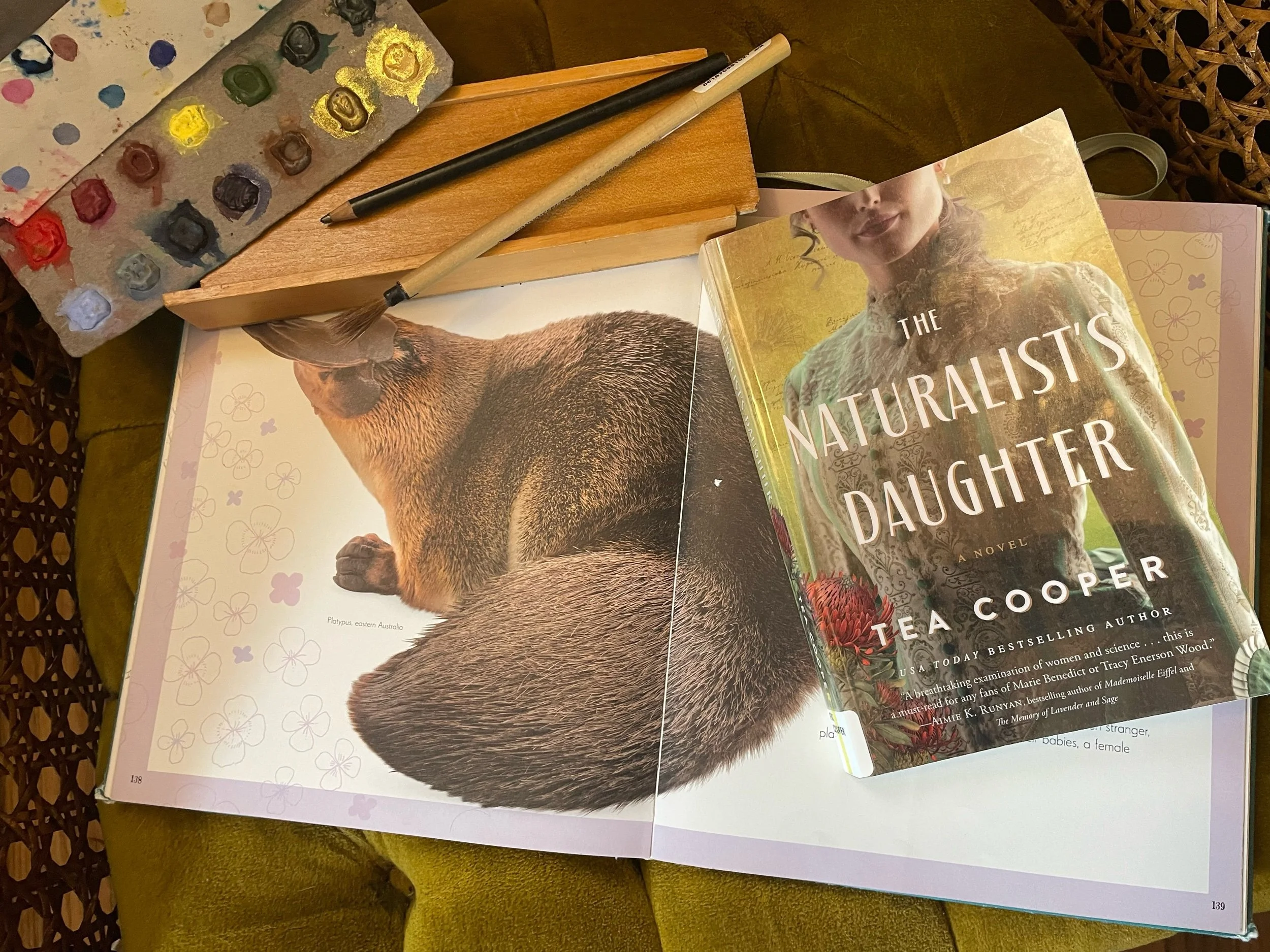

The Naturalist’s Daughter

Some books sweep the reader away to a specific place and time within the first lines. In the case of award-winning Australian writer, Tea Cooper’s novel, The Naturalist’s Daughter (2024), this certainly holds true. Cooper’s newest historical fiction opens amid the many oddities of a naturalist’s workroom in the backwaters of New South Wales, Australia. The year is 1808 and readers immediately meet the child Rose. She is a delightful young heroine who assists her father’s work which focuses on observing and documenting the curious creature now known as platypus (known by many names in the nineteenth century including Aboriginal mallangong). After introducing Rose, her father (Charles Winton) and her mother (Jennifer) along with a few Native folk,* Cooper interweaves a second storyline set one hundred years later (in 1908), also in New South Wales. This storyline, as with the first, champions an independently-minded young woman (Tamsin) who makes her own path rather than following the social conventions of the time. Rose’s story quickly jumps a decade in time and readers find her a young woman. As one might expect, the two storylines interweave and inform one another as the novel progresses. What’s more, the characters span the era of colonization (from the first ships) until the years following federation in 1901. In essence, then, The Naturalist’s Daughter encapsulates a slice of the early (Anglo) Australian experience. The Naturalist’s Daughter transports its readers to New South Wales, of both the early nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, while it fictionalizing the fascinating history on how the platypus was “discovered” and accepted by Western science.

Beyond its setting and fun historical information, The Naturalist’s Daughter provides parallel narratives of headstrong young women. Their adventures and budding romances make for entertaining reading. Yet, their stories tread into some dark paths and reveal the evil of which some men are capable. There is even an air of mysticism that creeps into the novel as their stories converge. The Naturalist’s Daughter sheds light on the wisdom of Aboriginal storytelling and highlights the misinformed arrogance of Western men of science. Indeed, the Royal Society’s motto states “Nullius in verba.— Take no one's word for it.” It is no accident that Cooper uses this as the epigraph for the novel. By taking no one’s word for some things, the educated Anglo Australians suffer.

Mystery lurks in the shadows of both Rose and Tamsin’s stories. As the two-pronged narrative progresses, both young women learn untold truths about their families and themselves. Both women must face difficult truths about their families just as they both find love in unexpected quarters. Inheritance, parentage, and the complexities that may linger below the surface in many a family all play a role in this compulsively readable historical fiction.

The Naturalist’s Daughter is the perfect read for those interested in arm chair travel. Traveling across the globe and back in time are two delightful perks of reading this novel (particularly if you do not currently find yourself in the antipodes). If you fancy a trip to nineteenth-century or early twentieth-century Australia, one that touches on early natural sciences of the platypus even, this is the ideal book for you.

*The novel opens with an author’s note explaining that it “employs the language of its era and historical setting” as a way of committing to “historical accuracy.” As promised, the novel consistently refers to Aboriginal people as “blackfellas.”

Bibliography:

Cooper, Tea. The Naturalist’s Daughter. Harper Muse: 2024.

A Great Passage:

"We blackfellas don't hold with pictures of people past. We remember our stories. Don't need pictures. Don't need writing it down” (283).