Gardens in the Dunes

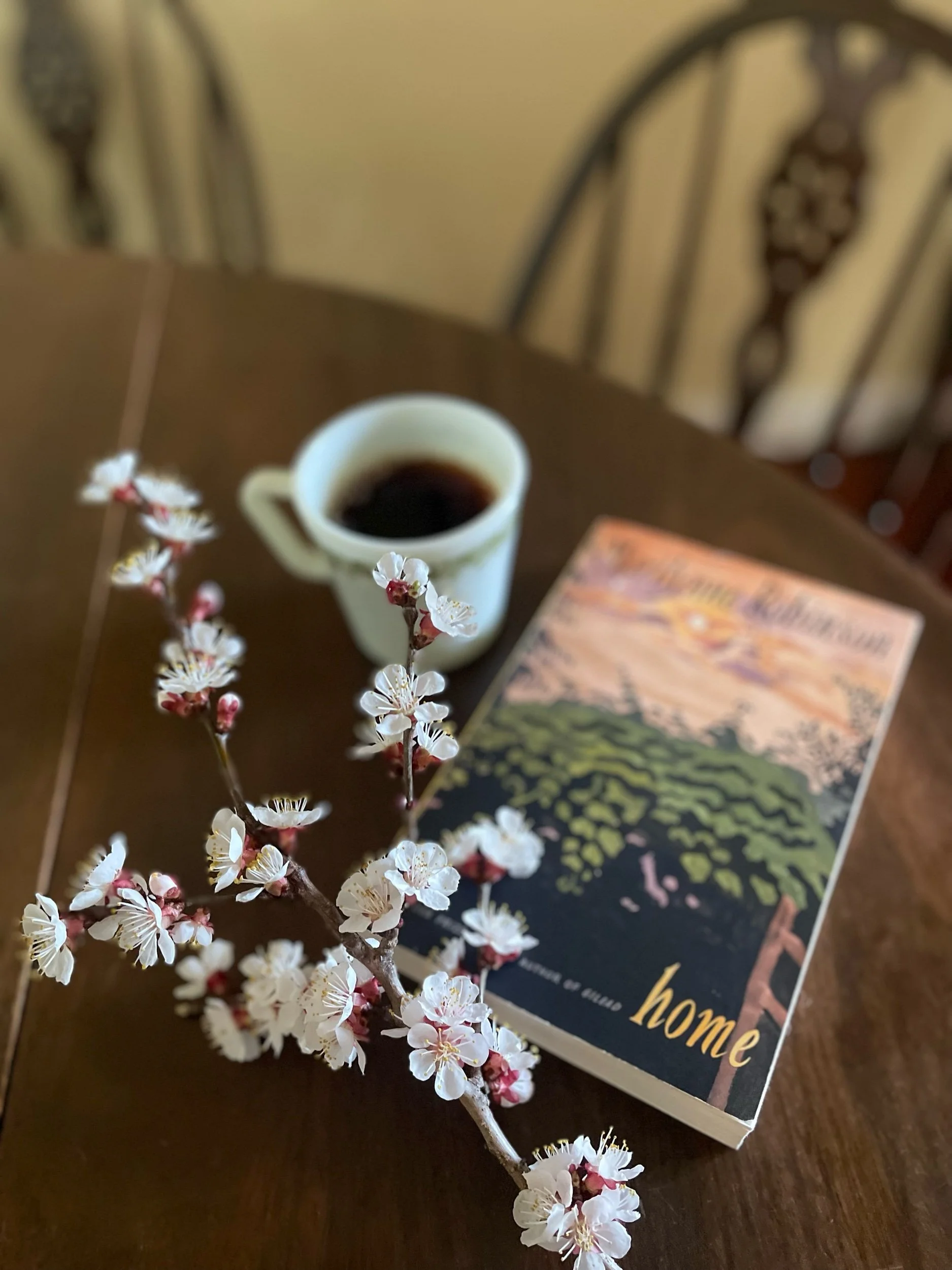

Leslie Marmon Silko was one of the first Native American writers I read. I read her famous story about a half-Pueblo man upon his return from serving in WWII, Ceremony (1977), over twenty years ago as an undergraduate. The mastery of her craft struck me all those years ago. She wove multiple stories together like twisted fibers in twine. I always meant to read more of her writing. Years passed. I finally acquired a copy of her chunky novel (just shy of 500 pages): Gardens in the Dunes (1999). More years passed. Finally, last autumn as I looked forward to a trip to New Mexico and Colorado, Gardens in the Dunes rose to the top of my to-read stack. The story immediately drew me in and I devoured its many pages quickly.

Gardens in the Dunes is a character-driven story about women and girls from wildly different backgrounds who all struggle to live authentically, to survive. It is historical fiction set during the end of the nineteenth century. One storyline begins in the dunes of Arizona that remain unsettled by Euro-Americans. There, readers meet some of the last remaining Sand Lizard People. The other storyline centers around members of American high society. An educated woman sheds a life of spinsterhood to marry a man of adventure, who she sees as a scientist. He has a complex history, gallivanting the world in search of rare plants to bring back, of which she knows only fragments of stories. All the characters’ lives, in time, become intertwined in what amounts to an incredible journey that stretches from California through the desert of the American Southwest, across Europe, and even to the jungles of Brazil. This novel scrutinizes the dominance of Euro-American cultural norms, which champion masculinity and material wealth, as it celebrates the complex exchange between myriad traditions in the lives of its central (female) characters.

Among the dunes two sisters, Indigo and Sister Salt, enjoy a short-lived childhood as they learn cherished traditions from their grandmother and recognize the danger of encroaching white culture. They are, they know, among the last of the Sand Lizard People. Despite their tribe’s near extinction, the girls learn their people’s language, ways, and values: matrilineal and sophisticated in terms of seed-saving, cultivation, and agriculture. The story centers upon Indigo, the younger of these sisters, however the reader certainly spends time with her elder sister, Salt, before the novel’s conclusion. Silko introduces readers to three generations of women in their family. Grandma Fleet tells the old stories and teaches by example. Mama eeks out a meager living twisting baskets to sell to white tourists at the train depot in Needles, Arizona; she finds refuge, when needed, at the dunes. Mama is liminal between worlds and drawn to the promise of salvation offered by the Messiah and a Paiute prophet named Wovoka. This Messianic movement, a second Ghost Dance, promises a return to the Native way of life and a rebirth of Earth; paradoxically the resulting gathering brings only destruction and diaspora to the participants. American soldiers break up the encampment of those surviving on the fringes, painted in white clay and dancing to welcome the coming Christ and their resurrected ancestors. The raid scatters the sisters’ family like poppy seeds in the wind. Yet, like seeds, the girls manage to survive even when forced to root outside the gardens in the dunes. Much of the novel, then, tells their stories on the long and meandering path home to the dunes and one another.

In contrast to Indigo and Sister Salt’s struggle to physically survive, readers meet Hattie Palmer whose struggle is psycho-emotional and intellectual, but no less real. Hattie is an academic, drawn to study of early women in the Church, for which she has been branded a heretic. She emerges from the shame and trauma of her failed academic career in theology by marrying Edward and moving from the salons of New York to the open country of Edward’s California estate. There she longs to cultivate the long-ignored gardens but chance leads her on a wild and unexpected adventure instead. She learns to value her own identity even when the dominant culture does not. Her life lessons certainly parallel those of Indigo and Sister Salt’s, as they all seek the refuge of being at home in the world.

Symbolism is huge in Gardens in the Dunes. Certain images and themes repeat throughout. One notable symbol is that of the sacred snake which Silko incorporates again and again in this novel; readers observe it as a creature guardian in the dunes and on ancient art across Europe. The sacred snake has long represented the feminine across cultures and time. Like the divine feminine, snakes shed their skin and embody death and rebirth. Silko expertly nods to the transcultural power of the serpent symbol by incorporating snakes throughout Gardens. Indeed, the serpent becomes a fulcrum of transformation and a symbol of survival and regeneration for individual characters and the novel generally.

Additionally, lest my many references to gardening and seeds, or the novel’s very title, fails to clearly communicate it, this is a novel that celebrates horticulture. Gardens can indeed grow among the sand dunes of the arid Southwest if they are carefully cultivated and stewarded. Gladiolus bulbs can be selectively bred to be a deep red, almost black. Also a symbol of the divine feminine, gardens are a place of refuge in this novel for many an independent female character.

In contrast to the feminine symbols of serpent and garden, Gardens in the Dunes also examines the flawed divinity of money. Nearly every male character—from Edward to Big Candy—pursues material gain blindly. Their stories become cautionary ones as the novel progresses and readers experience, through them, the loss and suffering that accompanies avarice. Also, within the context of its criticisms of an overly masculine culture are multiple scenes of sexual violence (readers be warned). In contrast to the masculine drive for money, young Indigo collects seeds on her journey as Grandmother Fleet taught her. She treasures her small parcel for the seeds and bulbs it contains all of which will bear food and ornamental flowers in the future. The beauty and life at the heart of Indigo’s collection quite literally promises to bloom in a riot of color and nutrients. It is a simple collection but arguably also the most wise and reliable. Thus, the novel’s youngest character seems to show us the way.

Silko’s novel is a brilliant blend of historical events, dynamic characters, and magical realism. Gardens in the Dunes incorporates the second Ghost dance and its fallout for both Native and Mormon settler participants. It examines Native experiences as prisoners at army forts and boarding schools. It’s characters include a Black, former slave who is a chef and business man, a wily circus-performing girl from Mexico who dreams of a better life for her people, and a number of independent women living in Europe. Suffice it to say, Silko wraps many a diverse species into the garden that makes up this novel.

Bibliography:

“Gardens in the Dunes by Leslie Marmon Silko.” Word by Word. June 15, 2019. Retrieved from: https://clairemcalpine.com/2019/06/15/gardens-in-the-dunes-by-leslie-marmon-silko/

Silko, Leslie Marmon. Gardens in the Dunes. Simon & Schuster: 1999.

A Few Great Passages:

“Anything could happen to us, dear,’ Grandma Fleet said as she hugged Indigo close to her side. ‘Don't worry. Some hungry animal will eat what's left of you and off you'll go again, alive as ever, now part of the creature who ate you.’ [. . .] dying is easy-it's living that is painful.’ [. . .] ‘To go on living when your body is pierced by pain, to go on breathing when every breath reminds you of your lost loved ones-—to go on living is far more painful than death’" (51).

“[W]hat a flawed vessel imprisoned the human soul!” (175).

“[I]f a garden wasn't loved it could not properly grow! She was an avid follower of the theories of Gustav Fechner, who believed plants have souls and human beings exist only to be consumed by plants and be transformed into glorious new plant life. Hattie had to smile; so human beings existed only to become fertilizer for plants!” (240).