A Pair of Blue Eyes

Thomas Hardy is famous for his later novels like Tess of the d’Urbevilles and Far From the Madding Crowd, but this winter I decided to pick up one of his early works, A Pair of Blue Eyes (originally published in 1873) and I did not regret it. A Pair of Blue Eyes was Hardy’s third novel (published serially) and the first he published under his own name. Parts of the novel are autobiographical and fans of Tess will note his early exploration of certain themes to which he returns later, but A Pair of Blue Eyes also stands alone as a great work and Hardy lovers ought not overlook.

In graduate school, many years back, I recall one of my professors telling us that Thomas Hardy wanted to write poetry, but his poems were too bleak for anyone to enjoy so he ultimately made his way to fiction. Whether that story is true or not, I went into reading A Pair of Blue Eyes prepared for tragedy and heart-break (many of Hardy’s most famous books are not known for their cheerful endings) and while I was glad I had, I also found myself utterly transported to nineteenth-century coastal England, specifically West Essex, with occasional trips to London. The melodrama that Hardy explores in the love triangle of the young architect (Stephen), his older mentor and literary critic (Henry Knight), and the young heroine Elfride, leads the reader through questions of young love, class, and the nature of devotion and marriage. Victorian novelists like Dickens moved away from the sentimental prose of the early nineteenth century (think Jane Austen novels) as they embraced realism and propelled the novel towards that genre. A Pair of Blue Eyes is certainly a reflection of this move toward realism and away from sentimentalism.

What’s more, Hardy arguably conceives of his two male protagonists by focusing on different aspects of himself. On the one hand is young, romantic Stephen who is committed to making the most of his life by pursuing architecture as a career (and leaving behind the agrarian peasantry of his family line). On the other Henry Knight is a literary critic and deep thinker who lives and works in London. Education connects the men initially, and ultimately their love of Elfride makes them rivals. Hardy himself trained to be, and worked as an architect, in his romantic youth. Likewise, he met his future wife when sent to do drawing of a gothic, rural church, just as Stephen and Elfride meet. Yet, Henry Knight, is also arguably a side of Hardy’s personality as the writer, intellectual and city-dweller. The tension between these protagonists and their rivalry for Elfride’s love takes on added dimension when the reader acknowledges the autobiographical elements of their character development.

Even in this earlier novel, Hardy’s poetic prose clings to realism. The novel mocks the romances popular in years past, suggesting the supremacy of realism both in its form and narrative. Yet A Pair of Blue Eyes leads the reader through romantic melodramas, amidst gothic churches and cemeteries and along the coastal cliffs with feeling. Hardy finds ways to invert romantic tropes and return his reader to reality, often with a jolt. The reader faces the complexity of Victorian romantic ideals and realities as Elfride pursues romantic love while seeing pragmatic financial decisions tied to marital ones as modeled by her father. While this is a novel in which the heroine falls in love not once but twice, realism trumps the sentimentality of a happy ending. Rather than tidy up one or the other romantic attachment, Hardy forces his protagonist to suffer the consequences of loving a man below her station first and then misrepresenting herself —through lies of omission—to her second beloved. Ultimately the novel’s tragedy reflects the realism for which Hardy’s novels are famous. Victorians may find romantic love, but that does not mean they will marry romantically, just as youth does not equate to long life.

If you, like me, fell in love with Thomas Hardy’s later works many years ago but have never read his early novels, this is one you will likely enjoy. As with some of his other early novels, the reader witnesses some of his favorite themes emerge. For those of us, like myself, committed to eventually reading every Hardy novel, observing this thematic progression throughout his oeuvre is fascinating and, I’ll admit, a bit thrilling.

A Few Great Passages:

“I am very far from knowing what life is. A just conception of life is too large a thing to grasp during the short interval of passing through it” (207).

“For a sensation of being profoundly experienced serves as a sort of consolation to people who are conscious of having taken wrong turnings. Contradictory as it seems, there is nothing truer than that the people who have always gone right don’t know half as much about the nature and ways of going right as those do who have gone wrong” (208).

as fine as possible on the other side of the clouds, she could not bring about any practical result from this fancy. Now, her mood was such that the humid sky harmonized with it” (229).

“There are disappointments which wring us, and there are those which inflict a wound whose mark we bear to our graves. Such are so keen that no future gratification of the same desire can ever obliterate them: they become registered as a permanent loss of happiness” (268).

“Male lovers as well as female can be spoilt by too much kindness, and Elfride’s uniform submissiveness had given Knight a rather exacting manner at crises, attached to her as he was” (340).

“The suspicious discreet woman who imagines dark and evil things of all her fellow-creatures is far too shrewd to be deluded by man: trusting beings like Elfride are the women who fall” (389).

Bibliography and Further Reading:

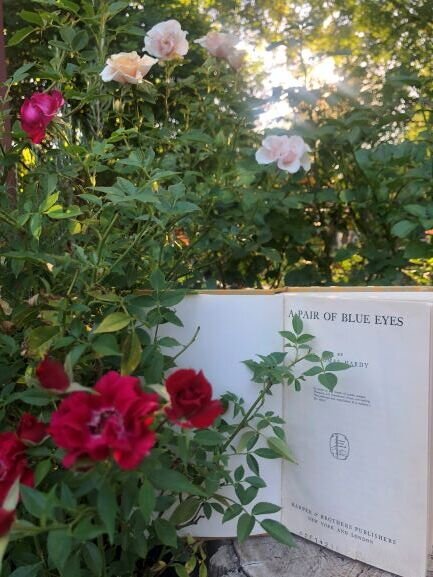

Hardy, Thomas. A Pair of Blue Eyes. Harper and Brothers Publishers: New York, 1895.

“A Short Analysis of Thomas Hardy’s A Pair of Blue Eyes”