Ghost Wall and Summerwater

Just like the ceaselessly falling rain, unusual even in Scotland’s wet climate, there is something eerie from the start in Sarah Moss’s Summerwater (2020). It was a similar feeling to that aroused by the opening scene of bog sacrifice in her Ghost Wall (2018). Both begin with scenes that portend harm, that set an ominous tone. And yet, there is also something so everyday about so much of the human experiences and interactions in Moss’s slight books. Something so recognizable takes form amid her characters. It is that tension—the foreboding and the mundane—that make her books so compulsively readable. The reader wonders, will she go there, will it get that dark, that startlingly disturbing; it is not until the final pages that the reader can grapple with answers to such questions.

I read Ghost Wall in the past year or so, and failed at the time to put words down about it. It is simple and succinct, fascinating, even terrifying at times. As I read it, I found it haunted me; a reality that continued long after finishing the short novella. Considering it now, many months after reading it, Ghost Wall still antagonizes and excites awe. This is fast read; I read it in one day. It is 130 pages, a slender novella. And yet, like the subjects it tackles—English nationalism, domestic violence, Iron Age Britons, bog people, and our modern fascination with what came before us—it is huge.

Ghost Wall is the first-person account of Silvie, a teenager with a wildly irregular father, who is entirely consumed by his hobby as an amateur archeologist. Hobby is truly too domestic a word; Silvie’s dad is obsessed with Iron Age British life. As a result, Silvie’s father takes archeology of Iron Age Britain beyond artifact; he wants to replicate life as it was. Ghost Wall follows the events that result from such a project. When her father teams up with an archaeology professor and some of his students, with Silvie and her meek mother in tow, they attempt to relive Iron Age life. Set in Northern England, Moss’s Ghost Wall introduces plenty of troubling themes alongside reflections of modern-day life. It is a book well worth the day’s read; one that readers will think about long after finishing.

Summerwater is also a short read, although slightly heftier than Ghost Wall. In it, Moss constructs an album of snapshot representing one community on holiday. Set in Scotland’s Trossach Park, Summerwater takes form through a series of first-person vignettes, separated by short lyrical reflections of nature, history, place. This novel bounces from one protagonist to the next: middle-aged parents, retired gentleman doctors, young affianced Gen Zers, young sleep-deprived mothers, dementia-rattled old women, children, teens. All ages, all stages of life, get a moment in the spotlight of Summerwater, as the reader occupies their varied perspectives and experiences. And yet, there are certain characters who sit outside the first-person narratives, outside the community: the Eastern Europeans staying in one of the cottages, the twenty-something military veteran camping in the woods. Summerwater explores the complicated and upsetting ways in which these individuals are at once excluded and also integral.

The word “summerwater” is the rain falling unendingly; the holiday on the loch; the wetness, somehow uncharacteristic in its steadiness despite the setting; a misremembered poem from childhood. Ultimately, it is the foreboding internal isolation of the myriad characters, across generations, all existing amid the ominous downpour. All existing together in a holiday park, where cabins are close enough to see and hear one another, and yet all alone. Summerwater highlights the paradox of holidays (vacations for we Americans) — togetherness alongside the loathing of constant community — and perhaps, by extension, modern life. It also demonstrates how community and climate are off kilter.

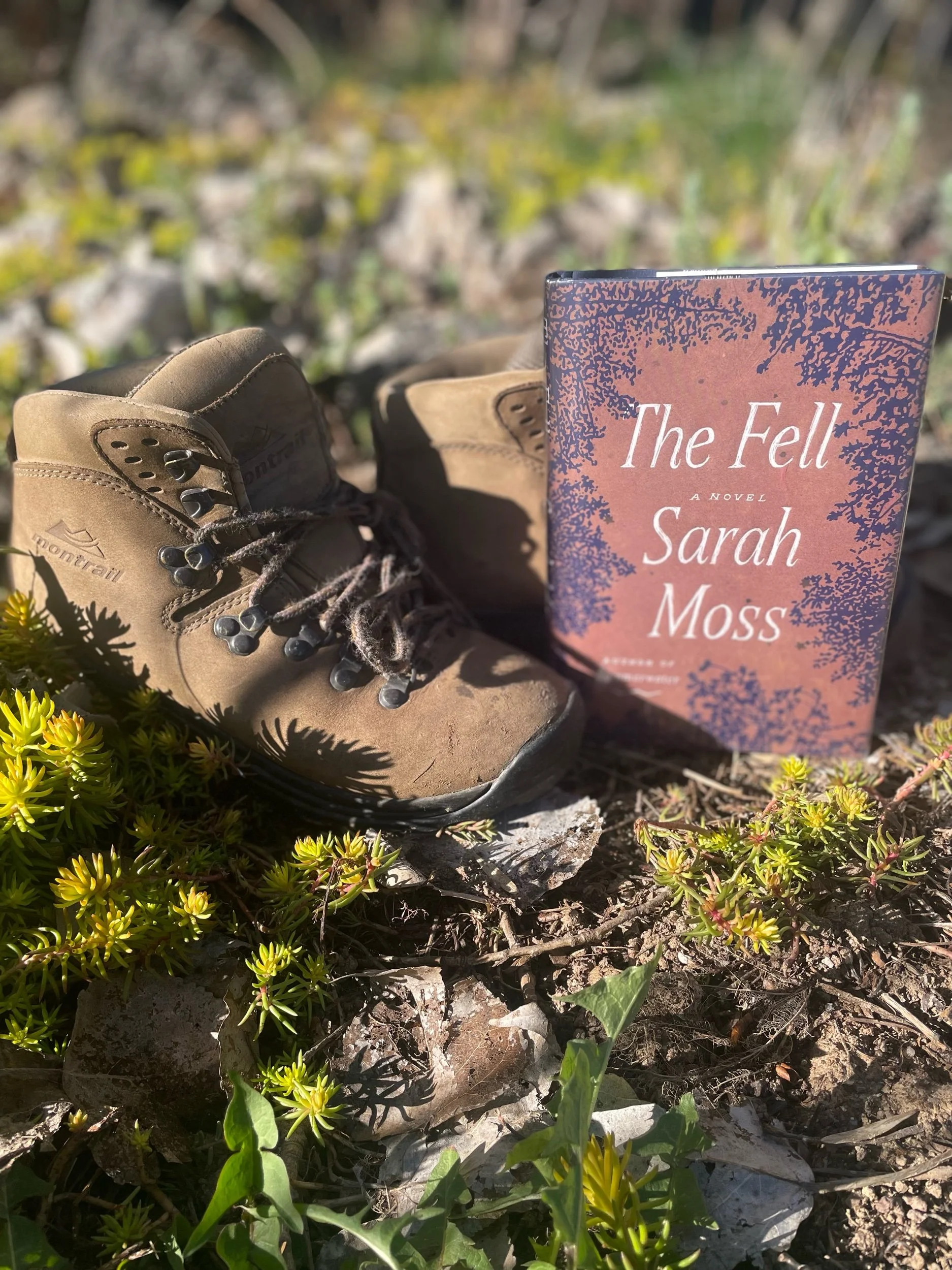

In both Ghost Wall and Summerwater, the intimate first-person point of views capture a range of troubling perspectives and cultural trends with which modern British people must contend. As an American, I would say many of themes Moss raises haunt American society as well, although perhaps in different garments. Moss’s writing is as moving as it is cutting. Readers will recognize themselves, their neighbors, family, and friends among her characters, particularly in Summerwater. These are unarguably cautionary tales, but their warnings draw we readers in and leave us plenty to chew over. I look forward to reading her most recent novel (also a short one), The Fell (2021), and grappling with the difficult questions, I am sure, it too will ask.

Bibliography:

Moss, Sarah. Ghost Wall. Picador: 2018.

------ Summerwater. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux: 2020.

A Few Great Passages:

“[H]e likes British prehistory, he thought it was a shame the old names had gone. Right, said Pete, you mean he likes the idea that there’s some original Britishness somewhere, that if he goes back far enough he’ll find someone who wasn’t a foreigner” (GW 18).

“If she’d known, she thinks, if she’d known that she wasn’t going to achieve the financial comfort or even security as the years went by, if she’d recognised the good times when she had them, she’d have travelled more when she was young, she’d have bought one of those train tickets, those passes, and gone everywhere [. . .] She’d have taken a year out, several years out, before settling” (S 6).

“He [. . . ] wonders what will be the last knowledge to leave him, will his neural pathways forget their own directions before he loses their map, will the city that’s been home all his life swirl and blur while he still holds all those medical-school mnemonics? Will he remember his mother’s long-buried face when he can no longer name the Prime Minister?” (S 37).

“There are other boats, below. There are the bones of skin coracles and shells of bark canoes and the hollowed-out trunks of trees that once gave shelter to bears. There are the small boats of boys in every century who never came home, and the water holds the hand-stitches of their clothes and the cow-ghosts of their shoes and the amulets that did not help when they were needed” (S 99).

“Not that kids don’t die for lack of interference and passing judgement, all those cases where decent folk minded their own business while neighbours beat and starved their children behind the net curtains. Quite ordinary people, sometimes. It takes a village to raise a child, isn’t that what they say? Someone has to be the village, to say what’s normal” (S 104-105).

“Maybe that’s all you need, really, a bed and a table. And bookshelves. People used to get by find didn’t they, before sofas and all that, generations of his family” (S 161).