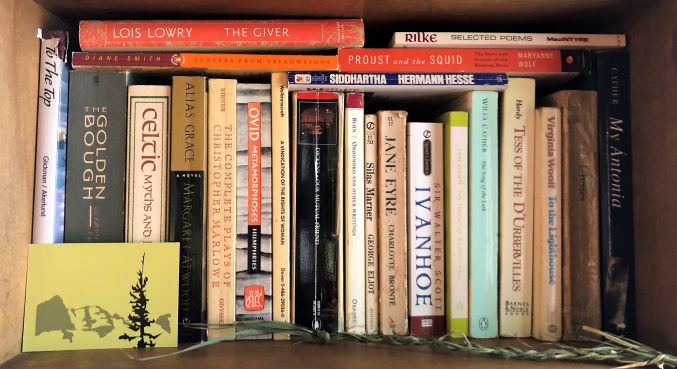

Letters from Yellowstone

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the publication, Diane Smith’s Letter’s From Yellowstone; it came out the same year I graduated from high school: 1999. This treasure of a book, however, didn’t find its way into my hands until much more recently. Perhaps it took me leaving Big Sky Country (after living in Montana for nearly a quarter century) to find myself pulling this book off my shelf and sitting down for a delightful, quick read.

Starting with its epigraph from Hamlet—”There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, / Than are dreamt of in your philosophy”—I adored Smith’s epistolary novel (literary speak for a book made entirely of written correspondence between its characters). A.E. Bartram (Alex to her friends, Alexandria to her family), is at once a lovable and fierce protagonist. Her first letter, dated March 10, 1898 from Ithaca, New York, finds its way to its addressee, Prof. H. G. Merriam, at the Agricultural College of the State of Montana (now MSU) in Bozeman, Montana. In this letter, Alex starts the plot rolling by stating she is “interested in exploring the complexities of plant life in their natural environs, and contributing to a scientific understanding of the plant kingdom” (3). To further recommend herself for field work in Yellowstone National Park, she describes herself as “young, single, and without any engagement to confine” her to New York (3). Of course, what she fails to mention is that she is female. In response to Alex’s letter, Howard Merriam, Ph.D., writes: “I am indeed planning a scientific expedition into Yellowstone. My goal is three-fold: to study Rocky Mountain specimens in their native setting and to initiate a collection of those specimens for a research herbarium I wish to establish here at Montana College. Based on this work, I plan to prepare a complete enumeration of Yellowstone and other Montana species” (4). Thus, the narrative unfolds as Prof. Merriam nervously awaits A. E. Bartram’s arrival and his leadership of an expedition (fraught with problems) into Yellowstone National Park in the summer of 1898.

What follows is a delightfully compelling and educational story about a fictional botany expedition into the wilds of late-nineteenth-century Yellowstone National Park. Smith inserts historically accurate details about the early years of Yellowstone National Park including cavalrymen stationed at the park and a young Native American family living quietly in its back country. As an ardent lover (and hobby sketcher) of wildflowers, I relished the botanical sketches of native wildflowers (labeled appropriately with their scientific names) with which Smith titles each section of her novel: Mimulus lewisii (monkeyflower), Lewisia rediviva (bitterroot), Calypso bulbosa (fairy slipper), Epilobium angustifolium (fireweed), and Rosa woodsii (wild rose). After completing the book, I enjoyed reflecting on what significance these section titles had to the story it contained.

I highly recommend this book to anyone who enjoys accurate history, witty prose, and scientific trivia sprinkled through even their light reads. Smith’s Letters from Yellowstone will not disappoint to transport its reader to the harsh, wild years of Yellowstone National Park one-hundred and twenty years ago. Through letter correspondence and the occasional telegraph, Smith develops, characters who are both inspiring and utterly human in their failures, frustrations and weaknesses. After I read this novel, I couldn’t wait to get outside hiking (and looking down) in search of some of my favorite wildflowers. And, of course, I longed to return to one of the magical places in the world: Yellowstone National Park.