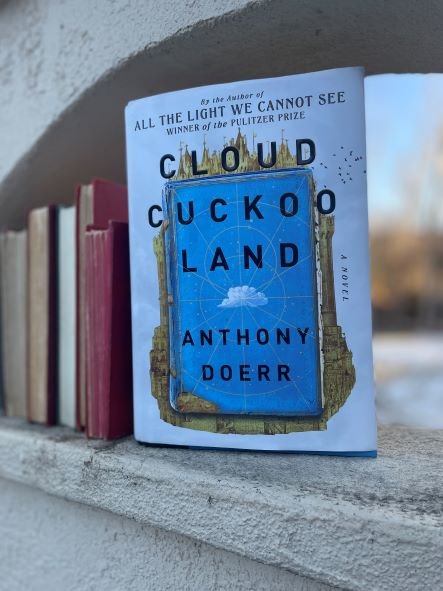

The Cassandra: A Novel

Mildred Groves lives in the tiny north-central Washington town of Omak, and as Sharma Shield’s novel The Cassandra (2019) opens, she interviews for a secretarial position at the Hanford site three hours south of her home town. The year is 1944. Wishing to contribute something beyond caring for her needy, verbally belittling mother, Shields’ protagonist longs to join the ranks of civil servants making their way to Hanford. But Mildred carries more than a desire to be a part of the patriotic cause; she sees the future, she recognizes her destiny, and she accepts it with excitement.

Named for the Cassandra of classical stories—youngest daughter of King Priam of Troy, who sees the future but whom the god Apollo curses with none believing her prophecies—Sharma Shields’ novel overlays Greek tragedy with 20th-century tragedy. The novel’s setting, therefore, feels very appropriate. The US built the nuclear bombs used on Japan at the close of WWII at Hanford, Washington. In fact, Hanford site existed only because of those bombs. When one thinks of the pinnacle of destructive wars in classical tales, the Trojan War comes to mind; World War II is the same for the last century. Placing Mildred at the Hanford site, with her uncanny ability to foresee tragedy that goes unbelieved by all, Shields’ novel tells the story of an understated (or often totally ignored) portion of American WWII history on the home front: the creation of Hanford outside of Richland, Washington and the complex realities of building the bombs, polluting the environment, and ravaging lives (both at home and abroad) in the process and aftermath.

In addition to linking Mildred to Trojan Cassandra, Shields alludes to a German heritage of soothsaying with Mildred’s memory of her grandmother (Ma Ingrid): “Wahrsager, she called herself” (Shields 21). Later, once Mildred arrives at Hanford, the “Aufhocker, [. . .] Shape-shifter” play a large role in her prophetic visions (Shields 67). Again, Shields recalls traditional German folklore of the Aufhocker, who (I discovered after cursory internet searches) is a dark creature, perhaps akin to vampires, that takes the shape of animals in order to teach a lesson. Along the tall cliffs of the Columbia River, Mildred meets Coyote and Blue Heron in her sleepwalking visions. As I read these surreal passages I thought of the blurring of reality/vision/dream often at work in Native American storytelling, and The Cassandra seems to allude to these traditions. Allusion to native storytelling techniques seems appropriate to the novel’s setting, in a place once sacred to the Wanapum along the mighty Columbia River:

Until a few months ago [before Hanford site was established], there had been a town here called White Bluffs, but the government had depopulated it in a handful of weeks, forcing residents out for little to no compensation. The Wanapum had been ordered out, too, urged north, out of their traditional fishing grounds. Boundaries reimagined and reordered, a process so sudden and unfeeling it almost seemed like an accident, as though the force determining it all was inhuman, a particularly destructive episode of weather, say, or a contagious disease. The people who had been here vanished (Shields 34).

Through a melting pot of storytelling traditions that explore the uncanny and prophetic, Shields’ The Cassandra, scrutinizes the sheer inhumanity of Hanford site’s project, the nuclear arms race, and environmental contamination, both in Washington state and across the world in Japan, that followed.

The darkness at work in The Cassandra builds as Mildred’s work at Hanford continues. Not only do her visions of the hibakusha, the victims of the Hiroshima bomb, grow darker and more imminent, but Mildred’s personal experience at Hanford takes a nasty turn. By the book’s close, the reader is left sorting through the many disturbing layers of destruction all of which humans are capable. There are moments in this novel during which I found myself wishing I had not experienced Mildred’s nightmarish visions, or the pain she suffers because of her gender and her gift of foresight, but then I recognized that those visions were real. The horrors of the hibakusha that Mildred foresees on the cliffs of the Columbia really happened. What’s more those horrors could again come to pass if any one of a growing number of international figures decides to launch a nuclear missile. Further, just as one powerful man (they are nearly all men in such power) might initiate nuclear war, so too The Cassandra points out, one man is capable of ravaging multiple lives through physical violence. And it is this reality check that I most appreciated about Shields’ novel. As The Cassandra reminds us, the US government created the two nuclear bombs dropped on Japan at the close of WWII and the moment those bombs fell our world changed forever after. As Shields suggests, many of the scientists who developed those bombs may not have imagined the true nightmare they unleashed with the weapon’s creation, but once nuclear arms existed, there was no going back. It is this horror of man’s ability to destroy life that The Cassandra unpacks—both on a global scale and on a personal one.

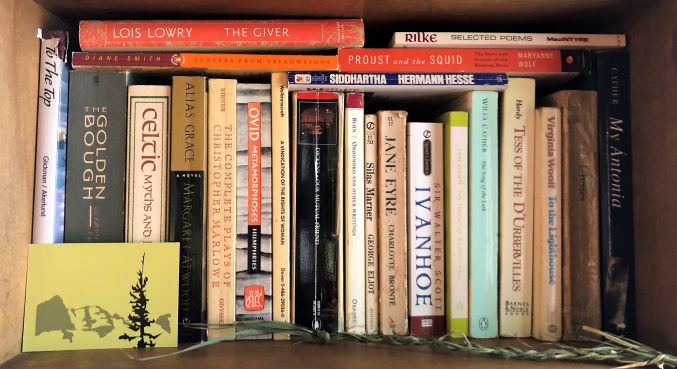

After reading The Cassandra, I at once, pulled out my copy of Aeschylus’s Orestia to reread Agamenon (the first of this set of Greek tragedies). Shields’ novel begins with three epigraphs, and a quotation from Aeschylus’s Cassandra is the third. I wanted to remind myself of the Greek tragic character, Cassandra, and after having read Shields’ twenty-first century retelling of her story, I found myself agreeing with Aeschylus’s Chorus: “The sayings of seers chime with evil. / The prophets teach men to know terror” (1134-1135). Cassandra’s final line in Agamenon—“I do not pity myself, I pity mankind” (Aeschylus 1330)—seemed to describe the way I felt at the close of The Cassandra. In a moment of subtle meta-narrative near the close of the novel, Mildred considers “[h]ow easily we trick ourselves into negating our empathy” (Shields 272). The Cassandra challenges its reader to recall that the horrors experienced through both Mildred’s vision and her life are not metaphor: “It’s happening in a novel but not in real life. It’s happening it’s happening it’s happening” (272). Nuclear war, betrayal, rape, murder, scientific failings, physical violence and environmental contamination all find their moment in The Cassandra, and resultingly its reader has the opportunity to empathize with, to even live, these horrors.

This is a book that is incredibly troubling and illuminating. It intimately reminds the twenty-first century reader of the horrors of nuclear war as well as the sheer destruction one man may bring about. Shields’ novel takes the reader through two devastations—one historic, one fictional. The Cassandra parallels the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasoki in August 1945 (a grand scale of man’s destructive capability) and the personal destruction of one woman and those whom she loves (an intimate scale of, perhaps, the same tendency). This is a book I will, no doubt, find haunts me with questions and considerations for many years; as such it is a book I encourage others to read so as to engage in the many difficult conversations begging to be had after reading a book like this.

A Few Great Passages from The Cassandra:

“Humans have only ever been at the mercy of one another, another that didn’t occur to me then, as I alighted in Hanford and smelled the fresh-cut wood and delighted in the new sights” (34).

“It fascinated me, the way Gordon spoke, so poetic and vulgar both, like a drunk scholar. Falstaff, I thought. It would be easy to listen to a man like this every day, as easy as it was to look at this face. I admired his stridency. I wanted to bake it, to eat it like a large meat loaf so that it would enter my bloodstream and become my own. But I sensed already, beneath his easygoing manner, a cruelty that could crush Tom Cat and me in an instant, and hesitantly, wrongly, I admired that, too” (43).

“Joining that great workforce, the flimsy weight of my girlhood dropped behind me on the ground like a discarded shawl” (49).

“‘Mildred, that’s enough. Shoulder’s back. You have a life to live. Choose to be strong. That’s all strength is, a choice’” (252).

“How easily we trick ourselves into negating our empathy.

It’s happening far away so it won’t happen here. It’s happening to someone else but not to me. It’s happening to the forsaken but not to my family. It’s happening in my mind’s eye but not in my neighborhood. It’s happening in a novel but not in real life. It’s happening it’s happening it’s happening” (272).

Bibliography:

Aeschylus, Oresteia. Translated by Peter Meineck, Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1998.

“Aufhocker” https://www.revolvy.com/page/Aufhocker, retrieved April 23, 2019.

Shields, Sharma. The Cassandra: A Novel. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2019.