On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (2019) by Ocean Vuong is a poetic, organic coming-of-age novel about a Vietnamese American child, Little Dog. Vuong crafts the novel as a letter of sorts that Little Dog writes to his illiterate mother. It is intimately personal, written in first person, as it bounces from point to point in the narrative of his childhood and adolescence.

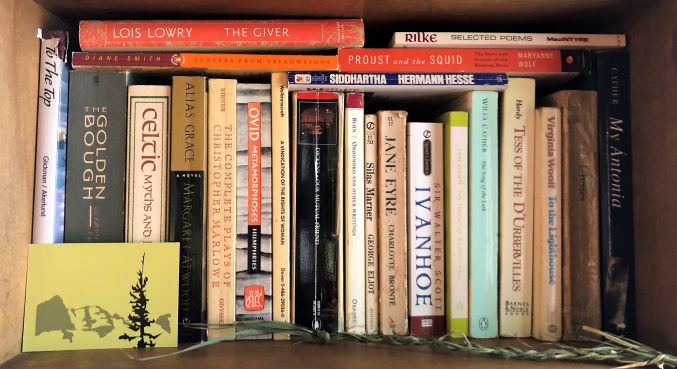

A few of my favorite reads…

CONTEMPORARY & CANONICAL ǁ NEW & OLD.

Fiction ※ Poetry ※ Nonfiction ※ Drama

Hi.

Welcome to LitReaderNotes, a book review blog. Find book suggestions, search for insights on a specific book, join a community of readers.